Etten (April – December 1881) · 3809 dagen geleden by Ad van den Ende

When Van Rappard departs from Brussels, Vincent also leaves Brussels.

12 April 1881 Vincent goes together with Theo to the parsonage in Etten. Now he has a clear target, and a great determination to attain that target. Thanks to Theo he is warm-heartedly welcomed by his parents.

“I’m very glad indeed that it’s been arranged for me to work here quietly for a while, I hope to make as many studies as I possibly can, for that’s the seed from which later drawings will grow. (…)

I’ve started on the Millets, The sower is finished and the 4 times of the day sketched. And now what is yet to come are The labours of the field. “ (30 April 1881)

The Sower, by Millet

He reads much. He has the opinion that art and literature go together. For him they are the key to a new moral philosophy.

In the beginning it is difficult to find models. Most of the people in Etten do not appreciate his behaviour. For them he is the failed son of the clergyman, a good-for-nothing. Vincent don’t let him down.

“My dear Theo,

It’s time that I wrote you a few lines again.

I must tell you that Rappard was here for 12 days or so, and has now left. Naturally he sends you his regards.

We went on a fair number of excursions together, several times to the heath at Seppe, among other places, and the so-called Passievaart, a huge marsh. There Rappard painted a large study (1 metre x 50 cm), much of which was good. Incidentally, he made around 10 small sepias, also in the Liesbos.5

While he was painting I made a pen drawing of another spot in the marsh where many water lilies grow. (Near Roosendaalseweg.)

The marsh near Roosendaalseweg

(…)

I’ve received Cassagne, Traité d’aquarelle, and am busy studying it, even if I don’t make any watercolours I’ll probably find a great deal in it anyway, as regards sepia and ink, for example.

Because up to now I’ve been drawing with pencil only, worked up or heightened with the pen, if necessary with a reed pen, which makes broader lines.” (Juni 1881)

In the surroundings of Etten he made his first landscapes. In this genre he was to excel in his later French work. He had a natural genius for finding simple but convincing subjects. The pen-and-ink drawing of the marsh near Roosendaalseweg is a good example of this. “Here he was exploiting his skill with the pen, but he could also capture landscape charasteristics flawlessly using other techniques as can be seen in the elongated picture of the Weeskinderendijk windmills in Dordrecht.” (Van Heugten)

“I was in The Hague until Thursday morning. Then I went to Dordrecht, because I’d seen a spot from the train that I wanted to draw. Namely the row of windmills. I got it done even though it was raining, and so at least I’ve brought home a souvenir from my outing. “ (26 August)

Row of windmills near Dordrecht

Vincent begins to draw his figures in the surroundings in which they work. He wants to portray “Brabant types”, busy with their daily activities.

“My dear Theo,

Even though I wrote to you only a short while ago, this time I have something more to say to you.

Namely that a change has come about in my drawing, both in my manner of doing it and in the results.

Prompted as well by a thing or two that Mauve said to me, I’ve started working again from a live model. I’ve been able to get various people here to do it, fortunately, one being Piet Kauffmann, the labourer.

The careful study, the constant and repeated drawing of Bargue’s Exercices au fusain has given me more insight into figure drawing. I’ve learned to measure and to see and to attempt the broad outlines. So that what used to seem to me to be desperately impossible is now gradually becoming possible, thank God. I’ve drawn

a peasant with a spade

no fewer than 5 times, ‘a digger’ in fact, in all kinds of poses, twice a sower, twice

a girl with a broom.

Also a woman with a white cap who’s peeling potatoes, and a shepherd leaning on his crook, and finally an old, sick peasant sitting on a chair by the fireplace with his head in his hands and his elbows on his knees.

And it won’t stop there, of course, once a couple of sheep have crossed the bridge the whole flock follows.

Diggers, sowers, ploughers, men and women I must now draw constantly. Examine and draw everything that’s part of a peasant’s life. Just as many others have done and are doing. I’m no longer so powerless in the face of nature as I used to be.

(…)

In short, ‘the factory is in full swing’, as Mauve says. “ (September 1881)

Worn Out

Etten, 12 Oct. 1881.

“My dear Rappard,

(…)

I’ve been drawing a lot from the models lately, since I’ve found a couple of models who are prepared to sit. And I have all kinds of studies of diggers, sowers &c., men and women. I’m working a lot with charcoal and Conté at the moment, and have also tried sepia and watercolour. Anyway, I can’t say whether you’d see improvement in my drawings, but most certainly a change.

(…)

You know what’s absolutely beautiful these days, the road to the station and to Leur with the old pollard willows, you have a sepia of it yourself. I can’t tell you how beautiful those trees are now. Made around 7 large studies of several of the trunks.

(…)

I’m absolutely certain that if you were here now when the leaves are falling, even if only for a week, you would make something beautiful of it. If you feel like coming, it would give all of us here pleasure.

Accept my parents’ warm regards and a handshake in thought from me, and believe me

Ever yours,

Vincent” (R.3)

Road to Leur

“Nature always begins by resisting the draughtsman, but he who truly takes it seriously doesn’t let himself be deterred by that resistance, on the contrary, it’s one more stimulus to go on fighting, and at bottom nature and an honest draughtsman see eye to eye.

Nature is most certainly ‘intangible’ though, yet one must seize it, and with a firm hand. And now, after spending some time wrestling and struggling with nature, it’s starting to become a bit more yielding and submissive, not that I’m there yet, no one is less inclined to think so than I, but things are beginning to go more smoothly. The struggle with nature sometimes resembles what Shakespeare calls ‘Taming the shrew’ (i.e. to conquer the opposition through perseverance, willy-nilly). In many things, but more particularly in drawing, I think that delving deeply into something is better than letting it go.

I feel more and more as time goes on that figure drawing in particular is good, that it also works indirectly to the good of landscape drawing. If one draws a pollard willow as though it were a living being, which it actually is, then the surroundings follow more or less naturally, if only one has focused all one’s attention on that one tree and hasn’t rested until there was some life in it. Herewith a couple of sketches, I’m rather busy in Leurseweg these days. Also work now and then with watercolour and sepia, but that isn’t immediately successful.”

(To Theo van Gogh. Etten, between Wednesday, 12 and Saturday, 15 October 1881)

Pollard Willow

Etten, 15 Oct. 1881.

“(…) Your comment on that figure of the sower — of which you said, it’s not a man sowing but a man posing as a sower — is very true.

I consider my current studies, however, to be studies from a model, they have no pretension of being anything else.

Only in a year or two will I get down to making a sower who is sowing, I agree with you there.” (R 2)

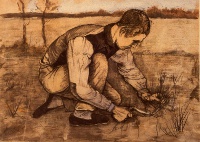

“(…) Today I again drew a digger, and since your visit a boy cutting grass with a sickle as well.

And also a man and woman sitting by the fire.11

Your visit was very pleasant for all of us, I’m so glad to have seen your watercolours, you’ve made a great deal of progress. (…)” (To Anthon van Rappard. Etten, Wednesday, 2 November 1881

Boy cutting grass with a sickle

“(…) HAVE MY DRAWINGS ARRIVED?6 I made another one yesterday, a peasant lad, in the morning, lighting the fire in the hearth where the kettle hangs, and another one, an old man laying dry twigs on the fire. I’m sorry to say that there’s still something stiff and severe in my drawings, and I think that she, namely her influence will be needed to soften that.” (To Theo van Gogh. Etten, Friday, 18 November 1881.)

Old man laying dry twigs on the fire

Vincent tended to show his figures from the side, to avoid problems of perspective.

“Occasionally he would hazard an attempt to a more complex view of a model. Without doubt the finest example of this is the man throwing dry twigs onto a fire. The figure is rendered in a very convincing way, not just from the front, but at a slight angle from above, a tour de force in which Van Gogh was completely succesful. Not only are the proportions convincingly rendered, but the artist has also managed to give the man and the simple interior an expression of weariness and frugality.” (Van Heugten)

“ (…) Have started another digger, busy digging up potatoes in the field. And there the surroundings are dealt with more thoroughly. Woods in the background and a strip of sky.

How beautiful the field is, old chap! When I earn more and can spend more on models, I’ll make entirely different things, you’ll see!

But it’s hard work for the models too, believe me. The more so because those I use aren’t professional models, and perhaps that’s all the better!”

(To Theo van Gogh. Etten, Saturday, 19 November 1881.)

Digger

The relation with his parents becomes worse when Vincent falls madly in love with his cousin Kee vos. She says: “No! Never!”

Man with a broom

Vincent took pleasure in taking advantage of prepared work. We see this man, on a reduced scale, in:

Way with willows and a man with a broom

He tried to build up a supply of figures in all sorts of positions which he could use in greater compositions.

His early work goes to show that Vincent takes much pleasure in working up his subjects. Before beginning to draw he always attempted to develop a feeling of sympathy for the subject. When he drew someone’s portrait he kept on talking with her or with him to keep the expression of the face lively.

He has an argument with his father who finds the books, Vincent reads, immoral. He decides to go for a few weeks to his cousin, the painter Mauve, in The Hague.

Anton Mauve was an outstanding painter of the Hague School. This school attempted to combine the ideals of The School of Barbizon with the ideals of the Dutch landscape-painters of the seventeenth century.

The School of Barbizon

Barbizon was a little village on the west-edge of the forest of Fontainebleau. Between 1830 and 1850 it was a refuge for many painters who wanted to experience there their love for nature, often in a pathetical mood. They had special attention for the beauty of the fertile earth and for the lives of the peasants. In the forest they made sketches and they worked them up in their studios.

Theodore Rousseau became their mentor. Other significant painters were: Jean François Millet, Jules Dupré and Charles Daubigny. The Dutch painter Jongkind worked there too.

From the end of November to the middle of December 1881 Vincent worked at Mauve’s studio. He painted during the day and drew in the evening. Mauve taught him the technique of watercolour drawing. Vincent drew several large watercolours and a number of smaller works.

Mauve also taught him that he was studying his models at to close quarters; so it was not possible to assess the proportions properly.

Vincent also learned that too much detail detracted from the principal motif. From then on he tried to give a more generalized view.

At Christmas 1881, after a violent argument with his father, he left Etten. He went to The Hague. Vincent was twenty-eight years old.