Youth · 3832 dagen geleden by Ad van den Ende

Vincent van Gogh, artist and author

Vincent Willem van Gogh (30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a post-impressionist Dutch painter whose work had a far-reaching influence on 20th-century art. After years of painful anxiety and frequent bouts of mental illness, he died aged 37 from a gunshot wound. His work was then known to only a handful of people and appreciated by fewer still.

“Van Gogh educated himself in ten years from an old-fashioned artist (…) up to one of the most prominent modernists of his time.(..) The threads which lead from his old to his late work are revealing for the artistic skill of Van Gogh.” (Axel Rüger)

“Van Gogh’s capacity in getting his meaning across to the public as an artist has been nourished and strengthened by varying experiences in his early life. The numerous unsuccesful attempts to make a career – as art dealer, teacher and assistant clergyman – have to be considered a false start and have not diverted him from his ultimate goal. They were of great importance for he forming of his artistry.” (Belinda Thomson)

Vincent’s interest in art began at an early age. He began to draw as a child and continued making drawings throughout his life. His early drawings do not approach the intensity he developed in his later work.

“The energy and vibrancy of his graphic style fed into his paintings. In turn, his drawings were informed bij the brilliance and luminosity of his paintings. Many of his drawings were intended as works of art in their own right, and at their best they surely count among his finest creations as an artist.” (Van Heugten)

He did not begin painting until his late twenties. In just over a decade, he produced more than 2,100 artworks, consisting of 860 oil paintings and more than 1,300 watercolours, drawings, sketches and prints. His work included self portraits, landscapes, still lifes, portraits and paintings of cypresses, wheat fields and sunflowers.

His youth 1853 – 1876

On March 30, 1852, a dead son was born at the house of minister Theo van Gogh and his wife, but a year after on the same date Anna van Gogh gave birth to a healthy boy. Him were given the names of the still-born first, Vincent Willem, after his two grandfathers. On the graveyard next to the church there was a tombstone with Vincent’s name and the date of his birthday: VINCENT WILLEM van GOGH March 30. Every Sunday Vincent passed that tombstone. One of his aunts felt pity for him. “Poor Vincent!” Did his parents have the same feeling, and is this the reason they were so “tenderhearted” for him, as Jo Bonger wrote? Did the children of the village kid him about it? Vincent must have felt himself a ‘substitue’ child’. Maybe for that reason he became shy and did not play with the other children out of the village.

“Theodorus van Gogh was a man of prepossessing appearance (“the handsome dominie” he was called by some), with a loving nature and fine spiritual qualities; but he was not a gifted preacher, and for twenty years he lived forgotten in the little village of Zundert ere he was called to other places, and even then only to small villages like Etten, Helvoirt, and Nuenen. But in his small circle he was warmly loved and respected, and his children idolized him.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Protestant church in Zundert

“Reverend Van Gogh belonged to a relatively moderate school of Protestant thought, the so-called Groningen school.This meant, among other things, that he considered dogma less important than the practice of Christian charity, and believed that God revealed himself not only in the Word, but also in creation itself, that is, in man and nature. All this culminated in a single exemplary figure, namely Christ. He was viewed as the personification of consolation in the biblical sense, the Consoler of the poor and weak.” (Leo Jansen)

“The married life of Theodorus van Gogh and Anna Carbentus was very happy. In his wife he found a helpmate who shared in his work with all her heart. Notwithstanding her own family and the work which it entailed, she visited his parishioners with him; and her cheerful, lively spirit was never dampened by the monotony of the quiet village life.

One of her qualities, next to her deep love of nature, was the great facility with which she could express her thoughts on paper: her busy hands, which were always working for others, grasped eagerly, not only needle and knitting needle, but also the pen. “I just send you a little word” was one of her favourite expressions, and how many of these “little words” came just in time to bring comfort and strength to those whom they were addressed to.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Anna Cornelia painted with pleasure still lifes of flowers. Perhaps Vincent inherited from her his passion for drawing and painting.

In qualities and character as well as in appearance Vincent took after his mother more than after his father. “The energy and unbroken strength of will which Vincent showed in his life were, in principle, his mother’s traits; from her also he took the sharp, inquisitive glance of the eye from under the protruding eyebrows. The blond complexion of both the parents became reddish in Vincent; he was of medium height, rather broad-shouldered, and gave the impression of being strong and sturdy. This is also confirmed by his mother’s words, that none of the children except Vincent were very strong. A weaker constitution than his would certainly have broken down much sooner under the heavy strain Vincent put upon it.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Grandfather Vincent had six sons, three of whom became art dealers, including another Vincent who was referred to in Van Gogh’s letters as “Uncle Cent.” Uncle Vincent was partner of the French firm Goupil & Co, an art dealer with branches in Paris, London and The Hague.

Art and religion were the two occupations to which the Van Gogh family gravitated.

Four years after Vincent his brother Theo was born.

“The two brothers were strongly attached to each other from childhood (…) Their childhood was full of the poetry of Brabant country life; they grew up among the wheatfields, the heath and the pine forests, in that peculiar sphere of a village parsonage, the charm of which remained with them all their lives. It was not perhaps the best training to fit them for the hard struggle that awaited them both; they were still so very young when they had to go out into the world, and during the years following, with what bitter melancholy and inexpressible homesickness did they long for the sweet home in the little village on the heath.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Later on Theo would play the key role in Vincent’s life: his best friend, his adviser and the person who supported him.

Vincent had another brother, Cor, and three sisters: Elisabeth, Anna and Willemina,“Wil”. Wil was the sister Vincent loved most. He gave her drawings, and they wrote each other letters.

”As a child he was of a difficult temper, often troublesome and self-willed; his upbringing was not fitted to counterbalance these faults, as the parents were very tender-hearted, especially toward their eldest. (…) Little Vincent had a great love for animals and flowers, and made all kinds of collections. There was as yet no sign of any extraordinary gift for drawing. (…) For a short time he attended the village school, but his parents found that the intercourse with the peasant boys made him too rough, so a governess was sought for the children of the vicarage….” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Vincent was serious, silent and thoughtful. As a boy he liked wandering through the fields and woods around Zundert.

Perhaps to restrain him somewhat his parents sent him, when he was eleven, to a boarding school at Zevenbergen, about 32 km away. Vincent did not feel at home between four walls. He was distressed to leave his family home as he recalled later as an adult.

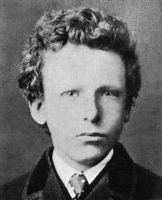

Vincent when he was thirteen

On 15 September 1866 he went to a new middle school in Tilburg. He was an average student. At school he developed a third passion next to walking and drawing: reading. He read prefarably about poor and persecuted people. During his long walks he saw the poverty and misery in the books he read confirmed in the lives of the peasants and labourers of West Brabant.

After one-and-a-half year he left school. His parents could not stimulate him to finish his studies. By now Vincent had sixteen months free for his three passions: walking, reading and drawing. Being the son of a clergyman he did not need to work on the land, like the other boys of the village. For them this was the preparation for their later profession. For Vincent these sixteen months had an opposite effect: the idea of an ordinary job – for instance the job as a baker, which his sister Anna later on would propose to him – was, after this undisciplined period, for him unthinkable.

Surrounding of Zundert

He took long walks with is father, when he visited his parishioners, who lived very scattered. Probably he was present at many talks of father Theo with his parishioners. Many peasants were very poor. For centuries weaving had been an important source of income for the peasants.This source did dry up fast because of the emerging textile industry. By means of his edifying conversation father Theo tried to give them hope and comfort. Probably this made a deep impression on the young Vincent. “Giving comfort” would become his ambition, first as a clergyman, later as a painter.

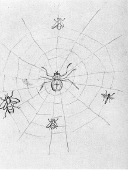

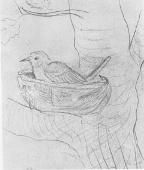

Walking together with his father Vincent got to know the surroundings of Zundert very well. His father drew his attention to the beauty of nature. When Vincent grew older he walked with pleasure during hours through the open country field in the neighbourhood of Zundert. On the way he tried to draw all he saw: for instance

and the post chaise en route from Amsterdam to Paris.

He drew also after models:

Together with Theo he collected drawings from (especially English) periodicals.

Perhaps he was as fanatical in drawing as in reading. Then he has made during his youth thousands of drawings. Only in that way it is explicable that he made such great drawings shortly after the beginning of his career as an artist.

Most of the drawings he made in his youth are not very beautiful. Particularly his shortage of knowledge of the perspective was playing tricks with him. Later, when he was in Drenthe, he wrote to Theo: “… how often I stood drawing on the Thames Embankment, on my way home from Southampton Street in the evening and it came to nothing. If there had been somebody then to tell me what perspective was, how much misery I should have been spared, how much further I should be now!”

The many hours he was drawing in his youth brought him nevertheless three important advantages:

1. he learned to observe carefully;

2. he learned what was important to reproduce;

3. he developed a marvellous drawing-handwriting.

His great familiarity with the peasants of West-Brabant would fit him very well later on in Etten and in Nuenen. People did trust him. To make his portraits lively he talked much with his models. The experience he gained during his youth gave him very much to talk about with them.

The Hague

His uncle Vincent helped him to obtain a position with the art dealer Goupil & Co in The Hague.

“Thus in 1869 Vincent entered the house of Goupil & Co., in The Hague, as the youngest employee under the direction of Mr. Tersteeg.

Goupil-shop in The Hague

His future seemed bright. (..) Tersteeg sent the parents good reports about Vincent’s zeal and capacities, and like his grandfather in his time, he was “the diligent, studious youth” whom everybody liked.

The shop was not far from

When he was seventeen or eightteen he made a drawing of De Lange Vijverberg which was not without merit. Also without perspective he suggests, by means of “side wings”, depth. The young man on the right is perhaps his first “self-portrait”. Later too he depicted himself gladly “en route”.

Except in paintings Goupil also was specialized in art-reproductions. Everyday Vincent was surrounded by works of art from all periods. He developed a fourth passion: looking at art. Except reading, drawing and walking he began to visit art galleries in his leisure hours. He familiarized himself very well with the art of the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

“When he had been at The Hague for three years, Theo (…) came to stay with him for a few days. It was after that visit in August, 1872, that the correspondence between the two brothers began, which was uninterruptedly carried on until Vincent’s death. And from this correspondence a by now faded, yellow, almost childish short half finished letter to Theo was found on him after his death with the desponding words que veux-tu? at the end and seems like a gesture of resignation with which he parted from life.

The principal events of both their lives are mentioned in the letters and are completed in this biographical notice by particulars, either learned from Theo himself, or found in the correspondence of the parents with Theo, which has also been preserved in full. (Vincent’s letters to his parents were unfortunately destroyed.) (…)

The letters tell of all the small events of daily life at the parsonage; what flowers were growing in the garden, and how the fruit trees bore, if the nightingale had already been heard, what visitors had come, what the little sisters and brother were doing, what the text of Father’s sermon was, and among all this, many particulars about Vincent.

London

He traveled to London via Paris, where he visited le Musée du Louvre. Afterwards the name of the painter Eugène Delacroix often occurs in Vincent’s letters. His relaxed and nevertheless inspired way of working made a deep impression on Vincent.

“At first everything went well with him in London; Uncle Cent had given him introductions to some of his friends, and he threw himself into his work with great pleasure. He earned a salary of £90 a year, and though the cost of living was high, he managed to lay by some money to send home now and then. He bought himself a top hat like a real businessman – “You cannot be in London without one” – and he enjoyed his daily trips from the suburbs to the gallery on Southampton Street in the city.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

He visited the art galleries and saw “View on the waterway” by Johan Hendrik Weissenbruch. This painting reminded him of the walks and good conversations with his brother Theo.

In London he admired also The Hay Wain by John Constable.

He gave Theo a great deal of advice:

“Man is not placed on the earth merely to be happy; nor is he placed here merely to be honest, he is here to accomplish great things through society, to arrive at nobleness, and to outgrow the vulgarity in which the existence of almost all individuals drags on.” (33, Londen, 8 mei 1875)

In London he reads with even more fervour English authors: Charles Dickens, Thoma Carlyle and George Eliot. From Eliot he reads among other books “Scenes of Clerical Life”. Especially the main character of the last story appeals to him, a clergyman who works in the slums of a big city. On his deathbed he is cared for by a woman who was earlier an alcoholic, but has been converted by him.

Thomas Carlyle inspired the socialist movement of the eighties by means of pamphlets about social abuses. He turned against the established church and declared himself openly in favour of a come back to a life in accordance with the gospel.

Charles Dickens wrote moving and sometimes comic serials about orphan children in a hard, loveless world. Vincent read and reread them, often in French.

He had such a thorough command of this language that he had no trouble in reading authors as Emile Zola, the De Goncourt brothers and Jules Michelet. Michelet wrote books about history, in which he raised questions about humanity and freedom.

Emile Zola was the predecessor of naturalism. This was a reaction to the Romantic Movement, and resulted from the realistic movement. This trend aspired to represent reality as carefully as possible. The Naturalism went further and approached the human reality scientifically. Taboo’s were broken and human society was shown such as it was. Not again stories about kings, but about the man in the street, about workers and prostitutes. Why writing about beautiful things if war and misery dominated life everywhere?

There was a broad criticism of impressionism, but Zola defended this trend. The De Goncourt brothers also belonged to the Naturalistic movement and wrote about art. These writers all propagated social justice and humanity, and turned away from the establishment. They chose a more evangelical attitude to life.

Jo van Gogh-Bonger writes:

“The first boardinghouse he stayed in was kept by two ladies who owned two parrots. The place was nice, but somewhat expensive; therefore, he moved in August to the house of Mrs. Loyer, a curate’s widow from the south of France, who with her daughter Ursula ran a day school for little children. There he spent the happiest year of his life. Ursula made a deep impression upon him. “I never saw or dreamed of anything like the love between her and her mother,” he wrote to one of his sisters; and, “Love her for my sake.” (…)

In January his salary was raised, and until spring his letters remained cheerful and happy. He intended to visit Holland in July, and before that time he apparently spoke to Ursula of his love. Alas, it turned out that she was already engaged to the man who boarded with them before Vincent came. He tried everything to make her break this engagement, but he did not succeed.”

12 November, 1881, Vincent wrote toTheo: “What kind of love did I have in my 20th year?7 Difficult to define, my physical passions were very weak then, perhaps owing to a couple of years of dreadful poverty and hard work. But my intellectual passions were strong, and by that I mean that I was determined, without asking anything in return or accepting any favours, only to give but not to receive.

Absurd, wrong, exaggerated, haughty, arrogant. For in matters of love one mustn’t only take but also give, and conversely, not only give but also take.

He who turns aside to the right hand or to the left falls, there is no mercy for him. So I fell, and it was a miracle that I found my footing again.”

He found comfort with John Bunyan’s “Pilgrims Progress”. “Bunyan believed the simple workers and the poor people proved themselves to be most worthy of God’s mercy, because their humility, self-denial and forsaking of wordly wealth gave them a natural spiritual advantage.” (G.S.Keyes)

“With this first great sorrow his character changed; when he came home for the holidays he was thin, silent, dejected – a different being. But he drew a great deal. Mother wrote, Vincent made many a nice drawing: he drew the bedroom window and the front door, all that part of the house, and also a large sketch of the houses in London which his window looks out on; it is a delightful talent which can be of great value to him.”

(…)

For the first time he was described as eccentric. His love for drawing had ceased, but he read a great deal. The quotation from Renan which closes the London period clearly shows what filled his thoughts and how high he aimed even then: “… to sacrifice all personal desires…to realize great things…to attain nobility and to surmount the vulgarity of nearly every individual’s existence…” He did not know yet how to reach his goal.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

In October, 1874, he was transferred to Paris. There he admires in Le Louvre “The Storm” by Jaob van Ruysdael. At an auction he sees a hall with drawings by the peasant-painter Jean-François Millet. When Vincent sees this his first thought is: “Take your shoes off your feet, for the place you stay on is holy ground.”

In his appartment he pins up among others a print of “View on Harlem” by Jaob van Ruysdael, jusy as a print of “The men of Emmaus” by Rembrandt.

From December 1874 up to 15 May 1875 he was active in London again.

“In May, 1875, he was transferred permanently to Paris and assigned especially to the picture gallery, where he felt quite out of place. He was more at home in his “cabin,” the little room in Montmartre where, morning and evening, he read the Bible with his young friend, Harry Gladwell, than a member of the mundane Parisian public.

His parents inferred from his letters that things were not going well. After he had come home at Christmas and everything had been talked over, Father wrote to Theo, “I almost think that Vincent had better leave Goupil within two or three months; there is so much that is good in him, yet it may be necessary for him to change his position. He is certainly not happy.” And they loved him too much to persuade him to stay in a place where he would be unhappy. He wanted to live for others, to be useful, to bring about something great; he did not yet know how, but not in an art gallery.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

He became increasingly isolated and fervent about religion; he became resentful at how art was treated as a commodity. On 1 April, 1876, Goupil terminated his employment.