The Hague (december 1881 – september 18830) · 3800 dagen geleden by Ad van den Ende

During four years Vincent worked in the Hague branch of Goupil. He knew The Hague very well, and he knew there were excellent possibilities to educate himself.

Vincent finds a chamber in the third sidestreet of the Schenkweg, on the border of the city and the countryside. He takes pleasure in his life, and the fact that he, thanks to Theo, is capable to furnish his own studio he finds too good to be true.

In The Hague Vincent holds on to his favourite subjects. He admires the old Dutch masters, their true factual pictures and their vitality. He considers them to be the source of the modern naturalist art of the School of Barbizon and the School of The Hague. In their landscapes man is represented in harmony with nature. Vincent thinks traditional subjects and modern art go together very well.

Constantly he looks for new ways in order to be a modern artist. In The Hague he considers the reproduction of compassion for the unhapy people in society his most important task.

At Blok’s bookshop he may choose for five guilders the most beautiful woodcuts from the English journals the Graphic and London News; woodcuts which have as a theme depressing social questions.

Bookseller Blok

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Sunday, 8 or Monday, 9 January 1882

“Now I thank you very much indeed for what you sent.

I don’t need to tell you that I really have a great many worries besides. Naturally my expenses are more than in Etten and I can’t set to work with half as much energy as I should like and should be able to if I had more at my disposal.

But my studio is turning out well. I wish you could see it, I’ve hung up all my studies, and you must send back the ones you have because they might prove useful to me. They may be unsaleable, and I myself acknowledge all their faults, but they contain something of nature because they were made with a certain passion.”

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Saturday, 14 January 1882

“I’m planning to go on making small pen drawings whenever possible, but different from the large ones I made this summer. A bit sharper and a bit angrier.

This is a sketch of Schenkweg, the view from my window

Well, adieu, with a handshake.

Ever yours, Vincent”

Schenkweg

Vincent’s “uncle Cor”, an art dealer, commissioned Vincent in the second half of March to make twelve townscapes. Vincent didn’t like to draw tourist attractions such as his uncle proposed.

Two weeks later this first series was finished. A view of the corner where the Herengracht and the Prinsessegracht meet was one of these townscapes.

Corner where the Herengracht and the Prinsessegracht meet

Another was a drawing of “The Paddemoes”, the fence of the teritory of the New Church. Vincent did not choose to draw the monumental church, but the street scene. He preferred to show the modern aspect of the city. Besides these drawings were for him studies in perspective.

Het Paddemoes

Uncle Cor commissioned a second series. This consists of larger drawings and has more appeal.

“In his view of a nursery garden and in another overlooking a carpenter’s yard and the laundry of the artist’s neighbour there is originality and daring in the compositions, and Van Gogh seems to be challenging the spectator by presenting so many different pictorial elements to capture his attention.” (Van Heugten)

View of a carpenter’s yard and the laundry of Vincent’s neighbour

The townscape became a permanentgenre in Vincent’s work.

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Friday, 3 March 1882

“My dear Theo,

Since receiving your letter and the money1 I’ve taken a model every day and I’m up to my ears in work.

It’s a new model I have, although I’d drawn her before superficially. Or rather it’s more than one model, because I’ve already had 3 people from the same family,

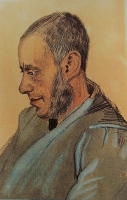

a woman of about 45

who’s just like a figure by E. Frère, and

her daughter, 30 or so,

and

a younger child of 10 or 12.

They’re poor people and, I must say, invaluably willing. I got them to pose for me, though not without difficulty and on the condition that I’d promise them steady work. Well, that was exactly what I wanted so very much, and I consider it a good arrangement.

The younger woman doesn’t have a pretty face because she has had smallpox, but her figure is very graceful and I find it charming. They also have good clothes. Black woollens and nicely shaped caps, and a pretty shawl &c.

You needn’t worry too much about the money, because we’ve agreed to compromise in the beginning. I’ve promised them a guilder a day as soon as I sell one. And that I’ll make it up to them later for giving them too little now.

But I must manage to sell something.”

The Hague (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

“The two years he spent there were for his work a very important period, of which his letters give a perfect description. His low spirits rose at first with the change of surroundings and the intercourse with Mauve; but the feeling of having been slighted and wronged did not leave him, and he felt utterly abandoned.

When in January he met a poor neglected woman approaching her confinement, he took her under his protection, partly from pity but also to fill the great void in his life. “I hope there is no harm in his so-called model. Bad connections often arise from a feeling of loneliness, of dissatisfaction,” his father wrote to Theo, who was always the confidant of both parties and had to listen to all the complaints and worries.

Father was not far from being right. Vincent could not be alone; he wanted to live for somebody, he wanted a wife and children, and as the woman he loved had rejected him, he took the first unhappy woman who crossed his path, with children that were not his own.

At first he feigned happiness and tried to convince Theo in every letter how wisely and well he had acted; the touching care and tenderness with which he surrounded the woman when she left the hospital after her confinement strike us painfully when we think on whom that treasure of love was lavished.

He prided himself now on having a family of his own, but when their living together had become a fact and he was continually associated with a coarse, uneducated woman, marked by smallpox, who spoke with a vulgar accent and had a spiteful character, who was addicted to liquor and smoked cigars, whose past life had not been irreproachable, and who drew him into all kinds of intrigues with her family, he soon wrote no more about his home life. Even the posing, by which she won him (she sat for the beautiful drawing, “Sorrow”) and of which he had expected so much, soon ceased altogether.

This unfortunate liaison deprived him of the sympathy of all in The Hague who took an interest in him. Neither Mauve nor Tersteeg could approve of his taking upon himself the cares of a family – and such a family! – while he was financially dependent on his younger brother. Acquaintances and relatives were shocked to see him walking about with such a slovenly woman; nobody cared to associate with him any longer, and his home life was such that nobody came to visit him. The solitude around him became greater and greater and, as usual, it was only Theo who understood and continued to help him.”

Soup distribution

To Theo van Gogh, The Hague, on or about Thursday, 6 April 1882.

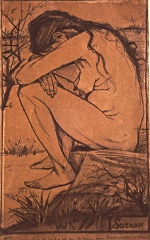

“What wonderful weather we’re having – there’s spring in everything. I can’t let go of the figure, for that’s No. 1 for me, but sometimes I can’t keep myself from going outdoors. But I’m busy with difficult things that I can’t let slide. (…)

The enclosed drawing was scratched after a larger study which has a more sombre expression. There’s a poem by Tom Hood. I believe, in which he tells of a great lady who can’t sleep at night because during the day, when she went out to buy a frock, she saw the poor seamstresses pale, consumptive, emaciated, working in an airless room. And now she has twinges of remorse about her wealth and wakes up at night in panic. In short, it’s a slender, white female figure, restless in the dark night.

(…)

A little drawing like the enclosed is simple enough in line, but it’s difficult enough to capture those simple, characteristic lines when one is sitting in front of the model. Those lines are now so simple that one can outline them with the pen, but I repeat, the problem is finding those broad outlines, so that one can say what’s essential with a couple of strokes or scratches. Choosing the lines in such a way that it’s obvious, as it were, that they must run thus, that’s something that isn’t obvious, however.”

Sorrow

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Monday, 10 April 1882.

“Naturally I don’t always draw like this. But I’m extremely fond of those English drawings that are done in this style, so it’s no wonder that I tried to do the same for once, and because it was for you, who understands these things, I didn’t hesitate to be somewhat melancholy. I wanted to say something like

But the heart’s emptiness remains

That nothing will make full again

as it says in Michelet’s book.”

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Monday, 1 May 1882

“I’ve now finished two larger drawings. First of all, Sorrow, but in a larger format, the figure alone without surroundings. But the pose has been altered somewhat, the hair doesn’t hang down the back but to the front, part of it in a plait. This brings the shoulder, the neck and back into view. And the figure has been drawn with more care.1

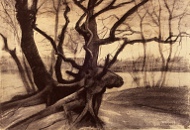

Roots

The other one, ‘Roots’, is some tree roots in sandy ground. I’ve tried to imbue the landscape with the same sentiment as the figure.

Frantically and fervently rooting itself, as it were, in the earth, and yet being half torn up by the storm. I wanted to express something of life’s struggle, both in that white, slender female figure and in those gnarled black roots with their knots. Or rather, because I tried without any philosophizing to be true to nature, which I had before me, something of that great struggle has come into both of them almost inadvertently. At least it seemed to me that there was some sentiment in it, though I may be mistaken, anyway, you’ll have to see for yourself.”

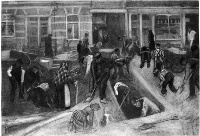

With the help of his figure studies Vincent wanted to build up a collection of separate figures out of which he later on could draw for the benefit of greater compositions. The figure of an

Old woman with a walking-stick and shawl

we see for instance again on two other drawings: on

Baker’s shop on The Geest

and on

Broken up street and diggers

We see that Vincent still had problems to fit separate figures in a greater whole, namely what concerns perspective.

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Sunday, 23 April 1882.(…)

“Enclosed is a little sketch of Diggers,

(…)

It’s precisely because I have a draughtsman’s fist that I can’t keep myself from drawing and, I ask you, have I ever doubted or hesitated or wavered since the day I began to draw? I think you know very well that I’ve hacked my way through and am obviously ever more keen to do battle.

Coming back to that little sketch – it was made in the Geest district in the drizzle, standing in a street in the mud, in all that bustle and noise, and I’m sending it to show you that my sketchbook proves that I try to capture things first-hand.

(…)

Struggling on wharves and in alleys and streets and inside houses, waiting rooms, even public houses, that’s not a nice job, unless one is an artist. As such one would rather be in the filthiest neighbourhood, provided there’s something to draw, than at a tea party with nice ladies. Unless one draws ladies, in which case a tea party is nice even for an artist.

I only mean to say that looking for subjects, frequenting the labourers, the struggle and worry with models, drawing from nature and on the spot, is all rough work – sometimes even filthy work, and truly, the manners and clothing of a shop assistant aren’t exactly the most appropriate for me or anyone else who doesn’t have to speak to beautiful ladies and wealthy gentlemen and sell them expensive things and earn money,a but instead draws diggers in a pit in the Geest district, for instance.

(…)

Do I lower myself by living with the people I draw, do I lower myself by frequenting the houses of workers and poor people or by receiving them in my studio? It seems to me that my profession involves that, and only those who understand nothing of painting or drawing are entitled to find fault with it.

I ask this: where do the draughtsmen for The Graphic, Punch &c. get their models? Do they or don’t they go themselves to round them up in the poorest alleyways of London? And the knowledge they have of the people, is it innate – or did they acquire it later in life by living among the people and by paying attention to things that most people walk right past, by remembering what many forget?”

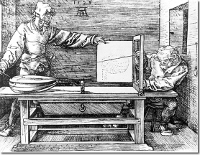

With the help of the textbook from Cassagne he depicted the row of trees and little gardens along the Country Road. But he was not always capable to estimate the proportions and perspective correctly. He knew that the German painter Albrecht Dűrer used a perspective frame.

In the second half of 1882 a friendly carpenter made such a frame for Vincent, with vertical, horizontal and diagonal threads.

In his landscapes lines, which are at right angles to the plane of the drawing, shoot, thanks to this frame, such as arrows into the depth.

Using this aid he produced Entrance to the Pawn Bank (803).

He drew the architecture of the bank and other buildings correctly. Later on he added the figures, but these are not correct: the two figures in the foreground are too big.

Vincent used the frame drawing a town- or a landscape, and also drawing figures. He would use it for the rest of his working life.

In the summer of 1882 Theo visited Vincent. He succeeded in persuading Vincent not to get married with Sien.

Theo advised Vincent the making of watercolours, becouse these were more saleable. At first Vincent hesitated, but later on he gave in.

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Tuesday, 4 July 1882

“Well brother, and during the move I’ve dashed off another drawing, a watercolour again. Based on a sketch done before my illness that was only half finished. So it’s coming to life again. It shows pinks on the beach,

big hulls of boats lying in the hot sand with the sea very far off in a blue mist or haze, for it was a day with sun, but it’s with the light behind, not into it, so that you have to feel the sun through a few short cast shadows and the shimmering of the warm air above the sand. It’s only an impression but I believe it’s fairly accurate.”

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Friday, 21 July 1882.

“Dear Brother,

(…)

People like me aren’t really allowed to be ill. You must really understand how I regard art. One must work long and hard to arrive at the truth. What I want and set as my goal is damnedly difficult, and yet I don’t believe I’m aiming too high. I want to make drawings that move some people. Sorrow is a small beginning — perhaps small landscapes like the

Laan van Meerdervoort,

the Rijswijk meadows and

the Fish-drying barn

are also small beginnings. At least they contain something straight from my own feelings.

Whether in figures or in landscapes, I would like to express not something sentimentally melancholic but deep sorrow.

In short, I want to reach the point where people say of my work, that man feels deeply and that man feels subtly. Despite my so-called coarseness — you understand — perhaps precisely because of it. It seems pretentious to talk like this now, but that’s why I want to push on.

(…)

This is my ambition, which is based less on resentment than on love in spite of everything, based more on a feeling of serenity than on passion.

Even though I’m often in a mess, inside me there’s still a calm, pure harmony and music. In the poorest little house, in the filthiest corner, I see paintings or drawings. And my mind turns in that direction as if with an irresistible urge. As time passes, other things are increasingly excluded, and the more they are the faster my eyes see the picturesque. Art demands persistent work, work in spite of everything, and unceasing observation.

(…)

I can now understand, better than six months ago or more, why Mauve said: don’t talk to me about Dupré, talk to me instead about the side of that ditch, or something like that. It sounds crude and yet it’s perfectly correct. Feeling things themselves, reality, is more important than feeling paintings, at least more productive and life-giving.

(…)

What I mean to say as regards the difference between old and contemporary art is: perhaps the new artists are deeper thinkers.

(…)

Rembrandt and Ruisdael are sublime, for us as much as for their contemporaries, but there’s something in the moderns that strikes us as more personally intimate.”

“The quick growth that Van Gogh was making as an artist can clearly be seen in a spectacular view looking out over the rooftops from his own house on the Schenkweg in The Hague. The perspective of the line of roofs seem to draw the spectator into the scene, which includes the already familiar carpenter’s yard and and the Rijnspoor station wedged between the road on the road and thehorizon.” (Van Heugten)

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Sunday, 23 July 1882.

“I’ll have a couple of watercolours for you when you come, brother. By Jove, the studio works so nicely. You remember, last winter I said: in a year you’ll have watercolours.

(…)

So you must imagine me sitting at my attic window as early as 4 o’clock, studying the meadows and the carpenter’s yard with my perspective frame — as the fires are lit in the court to make coffee, and the first worker ambles into

the yard.

Over the red tiled roofs comes a flock of white pigeons flying between the black smoking chimneys. But behind this an infinity of delicate, gentle green, miles and miles of flat meadow, and a grey sky as still, as peaceful as Corot or Van Goyen.

That view over the ridges of the roofs and the gutters in which the grass grows, very early in the morning and the first signs of life and awakening — the bird on the wing, the chimney smoking, the figure far below ambling along — this is the subject of my watercolour. I hope you’ll like it.

Whether I succeed in the future depends, I believe, more on my work than on anything else. Provided I can stay on my feet, well I’ll fight my fight quietly in this way and no other, that is by calmly looking through my little window at the things in nature, and drawing them faithfully and lovingly.”

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Sunday, 1 October 1882

“These last few days I’ve done almost nothing but watercolours. A scratch of a large one is enclosed. You may remember Mooijman’s state lottery office

at the beginning of Spuistraat. I passed it one rainy morning when a throng of people were standing there waiting to get lottery tickets. For the most part they were old women and the sort of people of whom it’s impossible to say what they do or how they live, but who evidently potter along and fret and get on with life. Of course, viewed superficially, a crowd of folk who evidently attach so much importance to ‘Draw today’ is something that almost makes you and me laugh, because we’re not in the least bit interested in the lottery.

But the group of people — and their waiting expression — struck me, and it took on a larger, deeper meaning for me while I was working on it than in the first moment. It becomes more meaningful, I believe, if one thinks of it as the poor and money. That, in fact, applies to nearly all figure groups: one occasionally has to think about them for a while before one understands what one is seeing. The curiosity and delusion about the lottery seem more or less childish to us, but it becomes serious when one thinks about the other side: misery and forlorn attempts by these poor souls to be saved, so they think, by buying a lottery ticket, paid for with pennies saved by going without food.

Be that as it may, I’m working on a large watercolour of it.

I’m also working on one of a church pew that I saw in a small church in the Geest district where the almsmen go (they’re known here very expressively as ORPHAN men and orphan women).

The way things are going, being busily drawing again, I sometimes think there’s nothing so pleasant as drawing.

This is part of the bit with pews; there are other men’s heads in the background.

Things like this are difficult, though, and won’t come off in one go. Success is sometimes the outcome of a whole string of failures. Speaking of orphan men, I was interrupted while writing this by the arrival of my model.

And I worked with him until it got dark — wearing a big old overcoat which gave him a curiously broad figure. I believe you might perhaps enjoy this collection of orphan men in their Sunday and working clothes.

Then I also tackled him sitting with a pipe. ( ) He has an interesting bald head — big ears (NB. Deaf) and white sideburns.”

With the help of a southwester he depicts the Orphan men as real sea dogs.

Later on, when he draws the peasants in Nuenen, he will have no longer use for this show element.

Vincent often thinks back to the Borinage. A coal porter at the ground of the station teaches him how to bear a sack of coals. Then Vincent draws the watercolour

Women who bear sacks.

In The Hague his drawing technique progresses enormously. “There comes action and character in the punctual rendered figures of workers and inhabitants of the house for the poor people – the so called Orphan Men – whom he represents in all their human dignity.” (De Jong)

Theo drew Vincent’s attention to a specific sort of paper. A drawing, made on it could be transferred to a stone. From this stone could be made one or more lithographs.

Vincent began to experiment immediately. He intended to make a series of about thirty litographs of “figures from the people for the people”.

Employees of the printer where Vincent had his litographs printed asked their boss for a copy of the litograph of The orphan man, wearing a big old overcoat.

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Thursday, 16 or Friday, 17 November 1882.

“I don’t know whether you’ll find it conceited of me or something like that when I tell you that the following gave me pleasure. Smulders’s workmen from the other warehouse in the Laan saw the stone of the orphan man and asked the printer if they could have an impression to hang up. No result of my work would be more agreeable to me than that ordinary working men should hang such prints in their room or workplace. I believe Herkomer speaks the truth when he says For you — the public — it is really done.

Of course a drawing must have artistic value, but in my view this shouldn’t rule out the possibility that ordinary passers-by may see something in it. Well, I regard this very first print as nothing as yet, but I hope from the bottom of my heart that it will become something more serious.”

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Wednesday, 22 November 1882

“My dear Theo,

Together with this letter you’re receiving the first proofs of one lithograph, Digger, and one lithograph,

Coffee drinker.

I’d very much like to know as soon as possible what impression they make on you.

I still plan to retouch them on the stone, and would like to have your opinion for that.”

More and more Vincent gets annoyed at Sien’s apathy and slovenly behaviour. He is not happy. That becomes clear out of the figures who express despair, such as

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Friday, 24 November 1882

“Today and yesterday I drew two figures of an old man with his elbows on his knees and his head in his hands.

(…)

What a fine sight an old working man makes, in his patched bombazine suit with his bald head.”

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, between Monday, 4 and Saturday, 9 December 1882

“Then one of the old boys with short jackets and big, old top hats one meets sometimes in the dunes.

He’s carrying home a basket of peat.

Now in these drawings I’ve tried to express my intention even more clearly than in the old man with his head in his hands. All these chaps are doing something, and I think that in general that, above all, should be adhered to in the choice of subjects. You yourself know how fine the numerous resting figures are, which are made so very, very often. They’re done more often than working figures.

It’s always very tempting to draw a figure at rest — expressing action is very difficult, and in the eyes of many the effect is ‘more pleasing’ than anything else.

But this pleasing aspect mustn’t lose sight of truth, and the truth is that there’s more toil than rest in life.“

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Sunday, 11 March 1883.

“In my view I’m often very rich, not in money, but rich (although not every day exactly) because I’ve found my work — have something which I live for heart and soul and which gives inspiration and meaning to life. My mood varies, of course, but nonetheless I have a certain average serenity. I have a certain faith in art, a certain trust that it’s a powerful current that drives a

person — although he has to cooperate — to a haven, and in any case I consider it such a great happiness if a person has found his work that I don’t count myself among the unfortunate.”

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Tuesday, 7 August 1883

(…)

My plan is not to spare myself, not to avoid a lot of emotions or difficulties. It’s a matter of relative indifference to me whether I live a long or a short time. Moreover, I’m not competent to manage myself in physical matters the way a doctor can in this respect.

So I carry on as one unknowing but who knows this one thing — ‘I must finish a particular work within a few years’ — I needn’t rush myself, for that does no good — but I must carry on working in calm and serenity, as regularly and concentratedly as possible, as succinctly as possible. I’m concerned with the world only in that I have a certain obligation and duty, as it were — because I’ve walked the earth for 30 years — to leave a certain souvenir in the form of drawings or paintings in gratitude. Not done to please some movement or other, but in which an honest human feeling is expressed.

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Monday, 10 September 1883.

Theo, I certainly have a feeling of melancholy on leaving, much more so than would have been the case had I been convinced that the woman would be energetic and that her good will wasn’t in doubt. Anyway, you know the gist from one thing and another. For my part I must press on or I myself will sink without getting her any further by that.

(…)

But the children to whom one’s heart goes out? I couldn’t do everything for them, but if only the woman had been willing!

(…)

I’ve equipped myself with an internal passport, valid for 12 months. With which I have the right to go where I will and to stay in one place for as long or as short as I please.

So I’m very glad that I can make progress, for in this way we help ourselves; (…)

So even if others won’t help, we won’t be idle.”

“In the twenty-one months in which Van Gogh worked in The Hague, he had developed into a young artist who was following in the footsteps of the masters of the Hague School such as Mauve and Josef Israëls (124-1911) and Barbizon artists such as Millet and Jules Breton (1827 – 1911), while he also derived great inspiration from works by artists in his own collection of graphic art.” (Van Heugten)