Nuenen (1883–1886) · Apr 5, 03:19 AM by Ad van den Ende

“His father had meanwhile left Etten and been called to Nuenen, a village in the neighbourhood of Eindhoven. The new place and surroundings pleased Vincent so much that instead of paying a short visit, as he originally intended, he stayed there for two years. He wanted to paint the Brabant landscape and the Brabant types, and in doing so he ignored every obstacle.

Living with his parents was very difficult for him as well as for them. In a small village vicarage, where nothing can occur unnoticed, a painter was obviously an anomaly; how much more a painter like Vincent, who had so completely broken with all formalities, conventions and with religion, and who was the last person in the world to conform himself to other people. On both sides there must have been great love and patience for it to have lasted so long.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Saturday, 15 December 1883

Dear brother,

I feel what Pa and Ma instinctively think about me (I don’t say reasonably).

There’s a similar reluctance about taking me into the house as there would be about having a large, shaggy dog in the house. He’ll come into the room with wet paws — and then, he’s so shaggy. He’ll get in everyone’s way. And he barks so loudly.

In short — it’s a dirty animal.

Very well — but the animal has a human history and, although it’s a dog, a human soul, and one with finer feelings at that, able to feel what people think about him, which an ordinary dog can’t do.

And I, admitting that I am a sort of dog, accept them as they are.

This home is also too good for me, and Pa and Ma and the family are so unduly fine (no feelings, though) and — and — they are ministers — many ministers. ”

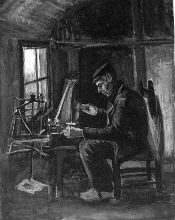

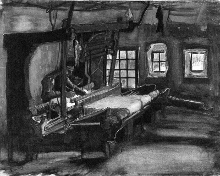

The weavers

“In Nuenen Vincent devoted himself at first to drawing. During the winter he made many sketches of weavers in their cottages. In 1879, on his long walking tour to visit Jules Breton, he had passed through wevers’ villages, and he had been impressed by the working people.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Sunday, 3 February 1884

“(…) You will certainly find the fact that I love the countryside here very understandable.

If you ever come I’ll take you into the weavers’ cottages sometime. The figures of the weavers and the women who wind the yarn will certainly strike you. The last study that I made is the figure of a onely man sitting at the loom, the body and the hands.(…)”

Between December 1883 and August 1884 Vincent made sixteen fully developed drawings showing weavers. These drawings show that he had gained in confidence. The drawings show weavers at work, behind their looms or engaged upon other activities, such as ordering the threads.

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Friday, 4 January 1884

For myself, I usually find it more pleasant among the people who don’t even know the word in question, for example the peasants, the weavers &c., than in the more civilized world. That’s fortunate for me.

So, for instance, I’ve been studying the weavers while I’ve been here.

Do you know many drawings of weavers? I only very few.

So far I’ve made 3 watercolours of them. These folks are difficult to draw because in the small rooms one can’t get far enough away to draw the loom. I think this is why attempts to do it usually fail. However, I’ve found a room here where there are two looms and where it can be done. Rappard painted a study of it in Drenthe, which I found beautiful. Very gloomy — for these weavers are very poor people.”

To Anthon van Rappard. Nuenen, on or about Thursday, 13 March 1884.

“My dear friend Rappard,

I was pleased with your letter about the drawings. As far as the loom is concerned, that really is a study of the machine made from start to finish in the place itself and was difficult — because one had to sit so close that it was very tricky to take measurements. I drew the figure in after all — but I don’t want to say anything with it except: ‘when that black monster of begrimed oak with all its slats somehow shows up like this against the greyness in which it stands, then there, in the centre of it, sits a black ape or goblin or apparition, and clatters with those slats from early till late’. And indicated the spot by setting down a sort of a shape of a weaver with a few scratches and blotches at the place where I saw him. Consequently, I didn’t give the slightest thought to the proportions of arms or legs at the time.

When my machine drawing had been finished fairly carefully, I found it so unbearable that I couldn’t hear it clatter that I let the apparition appear in it after all. Very well — and — say it’s only a machine drawing — just put it next to a design for a loom and — — — — — I tell you, mine will really be more HAUNTING. “

In 1890, after Vincent’s death, Van Rappard wrote to Vincent’s mother in a letter about the drawings of the weavers:

“How often I think of the studies of the weavers which he made in Nuenen and the intensity of feeling with which he depicted their lives; what deep melancholy pervaded his work, however clumsy its execution may have been then.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

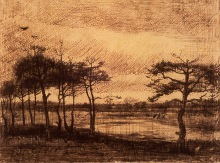

Landscapes

In March and April 1884 Vincent concentrated on landscape again. He made seven pen-and-ink drawings ”which display a quality that is exceptional in his Dutch œuvre. The promise of his earlier pen-and-ink landscape drawings is fulfilled in these sheets of drawings, which render a poetic and personal view of the Dutch landscape. Almost al the drawings (…) demonstrate his inventiveness in composition and his powerful drawing style. (…)

Pollard birches is one of the best examples of the soulful character Van Gogh was capable of injecting into his landscapes; he felt a great sympathy for these pruned trees with their striking, somewhat melancholy appearance.” (Van Heugten)

To Anthon van Rappard. Nuenen, on or about Thursday, 13 March 1884.

“My dear friend Rappard,

(…) Well, it pleases me that you like my little winter garden. This garden set me so to dreaming, and I’ve since made another of the same subject, also with a little black apparition, which yet again isn’t in it as an example of the structure of the human body worthy of imitating, but as a blotch. I’m sending you that one too, and a few others, sepia sketch:

pen drawing Pollard birches—

Behind the hedgerows —

and Winter garden. (…)”

To Anthon van Rappard. Nuenen, between about Friday, 21 and about Friday, 28 March 1884

“My dear friend Rappard,

My parents join me in asking you whether you would care — to come here one of these days. As soon as you like.

(…)

Outdoors — the trees are in blossom — and it’s precisely the time when it isn’t yet too hot for long trips.

Sent you another 3 pen drawings the other day,

Pine trees in the fen —

whose subjects I thought you would like. As far as the execution is concerned, of course I would wish right heartily that the direction of the pen strokes had followed the forms more expressively, and the forces that establish the tone of the masses also expressed their shape better. I think you’ll grant me that the way things fit together — the shape of them — hasn’t been systematically or deliberately neglected — but I had to make a rough stab at it in order somehow to render the effect of light and shade — nature’s mood at that moment — the overall aspect — in a relatively short time. For all three are specific moments that one can see these days.

(…)

Yours truly, Vincent” (R 45)

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, early April 1884

“What struck me in the scene was the astonishingly authentic and half old-fashioned, half rustic character of this garden. And the reason that I made no fewer than 3 pen drawings of the same little corner, as well as making several studies of it which I destroyed, was precisely because I wanted to convey this character in some intimate details that aren’t expressed easily or as a matter of course or by chance.

If, for my part, I have any self-confidence in my work, it’s also because it costs me too much effort for me to believe that one can’t gain anything by it or does it in vain. And yet again, I shrug my shoulders at the commonplaces into which most connoisseurs increasingly seem to be lapsing. “

Decoration of a dining room

To Anthon van Rappard. Nuenen, between mid-August and early September 1884

(…)

“This summer I saw a house in Eindhoven that belongs to a former goldsmith who is now rich, and has already amassed and sold a collection of antiques several times. This man paints a bit himself, and has a room in his house (which is full yet again of beautiful and ugly antiques) that he wants to paint himself.

He had a plan for it. When I went there, there were 6 panels, each 1 1/2 metres long by 60 cm high, which he still had to fill with something and on which he was planning to make, among other things, a Last Supper after a preliminary drawing that was in something like a modern Gothic style.

Then I said to him that in my view — since it’s a dining room — it would do considerably more to whet the appetites of those who would have to sit at table there if scenes from the peasant life of the region were to be painted on the walls rather than mystical last suppers. The good fellow didn’t contradict me. And after a visit to the studio, I made provisional scratches for him of 6 motifs from peasant life,

Shepherd,

And they’re what I’m doing now. But in such a way that I’m making these 6 canvases for myself, but that I’m making them, in terms of format, for instance, with a view to his room anyway, and he’s paying me my expenses for models and paint, while the canvases remain my property, however, and I get them back when he’s copied them. This lets me make things that would be rather too expensive for me if I were faced with the whole cost. And it’s a job I’m enjoying very much and working hard on. I’ll have to go to quite a bit of trouble, though, to point out things to him when he’s copying.

I’ve already got painted sketches in the finished size of something like 1 1/2 metres by 60 cm of Ploughman and Sower and Shepherd. Smaller ones of Wheat harvest and Ox-cart in winter. So you can imagine that I’m not exactly sitting on my hands these days.”

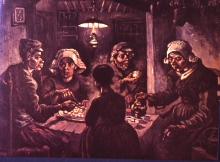

The potato-eaters

In december 1884 Vincent started on a series of heads of peasants. “Van Gogh saw peasants as rough and uncouth, but these were precisely the caracteristics that allowed them to be at one with nature in such an enviable way.” (Van Heugten)

It was “a way of life quite different of ours, from that of civilized people”, and “in many respects one so much better than the civilized world.” wrote Vincent.

Willem van de Wakker, one of his friends of that time, remembered: “He always chose the ugliest ones to model for him!” Another friend, Anton Kerssemakers, told about Vincent’s studio: “You were taken aback to see how full it was, paintings all over the walls and stacked on the floor, drawings in watercolour and in crayon, accentuating the boorish snub noses, jutting checkbones and big ears.”

Many drawings were studies for the great figure painting he was planning, The potato eaters. “The heads on many of the sheets of drawings are good likenesses, but only a few drawings are of outstanding quality, such as the one showing the careworn face af a peasant woman.

With her inward look she seems to stand as a symbol of the rigour of peasant life.” (Van Heugten)

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Friday, 23 January 1885.

“(…)

I’ve hardly ever begun a year that had a gloomier aspect in a gloomier mood, and so I don’t expect a future of success, but — a future of struggle.

It’s dismal outdoors — the fields a marble of clods of black earth and some snow, usually a few days of fog and mud in between — the red sun in the evening and in the morning — crows, shrivelled grass and withered, rotting vegetation, black bushes, and the branches of the poplars and willows vicious as wire against the dismal sky.

This, I see it in passing, and it’s quite in harmony with the interiors, very gloomy in these dark winter days.

It’s also in harmony with the physiognomies of peasants and weavers.

I don’t hear the latter complain, but they have a hard time of it.”

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, Thursday, 30 April 1885.

(…)

“You see, I really have wanted to make it so that people get the idea that these folks, who are eating their potatoes by the light of their little lamp, have tilled the earth themselves with these hands they are putting in the dish, and so it speaks of manual labour and — that they have thus honestly earned their food.

I wanted to give the idea of a wholly different way of life from ours — civilized people. So I certainly don’t want everyone just to admire it or approve of it without knowing why.

I’ve had the threads of this fabric in my hands the whole winter long, and searched for the definitive pattern — and if it’s now a fabric that has a rough and coarse look, nevertheless the threads were chosen with care and in accordance with certain rules.

And it might well prove to be a real peasant painting. I know that it is. But anyone who would rather see insipidly pretty peasants can go ahead. For my part, I’m convinced that in the long run it produces better results to paint them in their coarseness than to introduce conventional sweetness.”

“Mr. Kerssemakers recorded his reminiscences of that time in the weekly De Amsterdammer of April 14 and 21, 1912,

(…)

He also told about their trip to Amsterdam (in the autumn of 1885) to see the “Rijksmuseum,” how Vincent in his rough ulster and his inseparable fur cap calmly sat painting a few small views of the city in the waiting room of the station; how they saw the Rembrandts in the museum, how Vincent could not tear himself away from the “Jewish Bride” and said at last, “Would you believe it…I should be happy to give ten years of my life if I could go on sitting here in front of this picture for a fortnight, with only a crust of dry bread for food?” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

The peasant-drawings

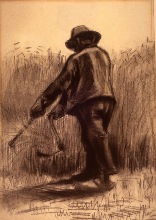

Vincent was dissatisfied because he thought his figures were to ‘flat’. He tried to find a solution for this problem by looking for a model to follow. He chose Eugène Delacroix (1798 – 1863). Vincent learnt from him “that he ought not to think in terms of lines and contours, but should identify the essential mass of a figure and depict it by large, rounded forms: egg-shapes or ellipses. He started off cautiously with small figures but soon took a liking to this system.” (Van Heugten)

This method worked for Vincent. He made a series of more than fifty drawings in accordance with this method. The quality of this peasant series is impressive.

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, Monday, 6 July 1885.

(…)

We need an art with strength and vigour, says Raffaëlli, and in achieving this in the figure one has so much difficulty finding models.

The time has passed, and I’m not complaining about it. Although it’s enough for a figure to be put together conventionally, academically – or actually, although many people want precisely that, there’ll be a reaction nonetheless — and I hope that will stir things up. The artists are calling for character, well — the public will do the same. (…)

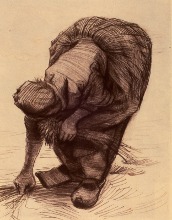

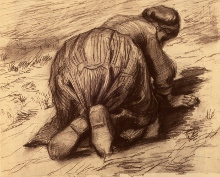

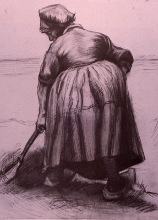

I’ve got a few figures here, a woman with a spade seen from behind, (933)

another one bending over to glean ears of corn — (930)

another one from the front with her head almost on the ground, digging up carrots.

I’ve been spying on these peasant figures here for 1 1/2 years and on their activities, precisely to get some character into it.”

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Tuesday, 14 July 1885

(…)

But I want to point out something that’s perhaps worth noting. All academic figures are constructed in the same way and, let’s admit, one couldn’t do better. Impeccable — without faults — you’ll already have seen what I’m driving at — also without giving us anything new to discover.

Not so the figures of a Millet, a Lhermitte, a Régamey, a Lhermitte, a Daumier. They’re also well constructed — but not the way the academy teaches, after all. I think that no matter how academically correct a figure may be, it’s REDUNDANT in this day and age, even if it were by Ingres himself (apart from his Source of course, because that indeed was and is and will remain something new) if it lacks that essential modernism — the intimate character, the actual DOING SOMETHING.

When will the figure not be redundant then, even though there were necessarily faults and grave faults in it to my mind, you’ll probably ask.

When the digger digs, when the peasant is a peasant, and the peasant woman a peasant woman. Is this something new? Yes. Even the little figures by Ostade, Ter Borch don’t work the way they do nowadays.

I’d like to say a lot more about this and I’d like to say how much I myself want to do what I’ve begun even better — and how much higher than my own I value the work of some others. I ask you — do you know of a single digger, a single sower in the old Dutch school??? Did they ever try to make ‘a labourer’? Did Velázquez try it in his water-carrier? Or his folk types? No.

Work, that’s what the figures in the old paintings don’t do. These days I’m slogging away at a woman whom I saw last winter, lifting carrots in the snow.16 There it is — Millet did it, Lhermitte, and in general the peasant painters of this century — an Israëls — they find that more beautiful than anything else.

But even in this century, how relatively few there are among the legion of painters who want the figure — yes — above all — for the sake of the figure (i.e. for the sake of form and modelling) but can’t conceive of it other than working, and also have the need — which the old masters avoided, as did the old Dutch masters who depicted so many conventional actions — and — I say — have the need to paint the action for the action’s sake. (…)

Showing the figure of the peasant in action, you see that is what a figure is — I repeat — essentially modern — the heart of modern art itself — that which neither the Greeks, nor the painters of the Renaissance, nor the painters of the old Dutch school have done.

To me, this is a matter I think about every day. However, this difference between both the greater and the lesser masters of the present (the greater, for instance Millet, Lhermitte, Breton, Herkomer; the lesser, for instance Raffaëlli and Régamey) and the old schools isn’t something I’ve often found expressed truly forthrightly in articles on art.

Just think about whether you don’t find it’s true, though. The figure of the peasant and the workman started more as a ‘genre’ — but nowadays, with Millet in the van as the eternal master, it’s the very heart of modern art and will remain so.”

In September 1885 Vincent was accused -falsely – of getting one of his models pregnant. A parish priest advised his parishioners to stop posing for Vincent. Fom now on he concentrated on drawing landscapes without human figures; the wheat itself attested to the splendour of country life.

This type of drawings and paintings he would continue to make until the end of his career.

But Vincent knew that he still had much to learn about human anatomy. In September 1885 he went to Antwerp.

Op dit artikel kan niet gereageerd worden.