Ramsgate, Amsterdam, The Borinage · 4206 dagen geleden by Ad van den Ende

Failed as a Clergyman

“It seemed that Theo, who was soon to become everybody’s helper and adviser, had already at that time suggested Vincent becoming a painter; but for the moment he would not hear of it. His father suggested a position in a museum or opening a small art gallery for himself, as Uncle Vincent and Uncle Cor had done before him; then he would have been able to follow his own ideas about art and no longer be obliged to sell pictures which he considered bad. But his heart drew him to England again, and he planned to become a teacher.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Vincent returned to England for unpaid work as a supply teacher in a small

boarding school overlooking the harbor in Ramsgate where he made sketches of the view.

Ramsgate, 31 May 1876

“Have I already written to you about the storm I saw recently? The sea was yellowish, especially close to the beach; a streak of light on the horizon and, above this, tremendously huge dark grey clouds from which one saw the rain coming down in slanting streaks. The wind blew the dust from the small white path on the rocks into the sea and tossed the blossoming hawthorn bushes and wallflowers that grow on the rocks. (…)

That same night I looked out of the window of my room onto the roofs of the houses one sees from there and the tops of the elms, dark against the night sky. Above those roofs, one single star, but a nice, big friendly one. And I thought of us all, and I thought of the years of my life that had already passed, and of our home, and the words and feeling came to me, ‘Keep me from being a son that causeth shame, give me Your blessing, not because I deserve it, but for my Mother’s sake. Thou art Love, beareth all things. Without your constant blessing we can do nothing.’”

When the proprietor of the institute relocated the school to Isleworth, Middlesex, Vicent moved with him. He took the train to Richmond and did the remainder of the journey on foot. The arrangement did not work out and he left to become a Methodist minister’s assistant, following his wish to “preach the gospel everywhere.”

“His letters home were gloomy. “It seems as if something is threatening me,” he wrote. His parents perceived full well that teaching did not satisfy him. They suggested his studying for a French or German college certificate, but he would not hear of it. “I wish he could find some work in connection with art or nature, wrote his mother, who understood what was going on within him. With the force of despair he clung to religion, in which he tried to satisfy his craving for beauty as well as his longing to live for others.“ (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Isleworth, November 1876

“My dear Theo,

It’s again high time that you heard something from me. Thank God you’re recovering, I long so much for Christmas – perhaps that time will come before we know it, even though it seems a long way off.

Theo, your brother spoke for the first time in God’s house last Sunday, in the place where it is written ‘I will give peace in this place’. I’m copying out what it was herewith. May it be the first of many.

It was a clear autumn day and a lovely walk from here to Richmond along the Thames, which reflected the large chestnut trees with their load of yellow leaves and the clear blue sky, and between the tree-tops the part of Richmond that lies on the hill, the houses with their red roofs and windows without curtains and green gardens, and the grey tower above it all, and below, the large grey bridge with tall poplars on either side, with people crossing it who looked like small black figures.

When I stood in the pulpit I felt like someone emerging from a dark, underground vault into the friendly daylight, and it’s a wonderful thought that from now on, wherever I go, I’ll be preaching the gospel – to do that well one must have the gospel in his heart, may He bring this about.“

The painting by George Henry Boughton: “God speed! Pilgrims on the way to Canterbury” inspires him when he gives this first sermon. Our life is a long journey upwards, a way full of suffering, and the redemption as a shining finish. The idea of our life as one long pelgrimage he will always keep in his mind.

At Christmas, 1876, he returned home and found work in a bookshop in tDordrecht for six months. He was not happy in this new position and spent much of his time translating passages from the Bible into English, French and German. Vincent’s religious zeal grew until he felt he had found his true vocation.

Etten, 1 April 1877

“On Saturday evening I left on the last train from Dordrecht to Oudenbosch and walked from there to Zundert. It was so beautiful there on the heath, even though it was dark one could make out the heath and the pine-woods and the marshes stretching far and wide, it reminded me of that illustration by Bodmer that’s hanging in Pa’s study. The sky was grey but the evening star shone through the clouds, and now and then other stars were visible too.

It was still very early when I arrived at the cemetery in Zundert, where it was so quiet, I went to have a look at all the old places and paths and waited for the sun to rise. You know the story of the Resurrection, everything there reminded me of it in that quiet cemetery this morning.”

Without a doubt he saw the tombstone with his name and the date of his birthday. Reminded this him of the Resurrection?

Evangelist in training (1877 – 1879)

The family gives Vincent permission to start a two-year preparation for the university entrance examination in Amsterdam, required for an eight-year theological study. He is twenty four. From the beginning he talked with Theo about his doubt whether he would see it through.

Amsterdam, 30 May 1877

“There were some words in your letter that touched me: ‘ I should really like to get away from everything, I’m the cause of everything and only make others sad, I alone have caused all this misery to myself and others’ . Those were words that touched me – because that same feeling, exactly the same, nothing more and nothing less, is also on my conscience.

When I think of the past – when I think of the future, of nearly insurmountable difficulties, of much and difficult work, which I have no passion for, which I – the evil part of me that is – would prefer to avoid, when I think of the eyes of so many that are fixed upon me – who, if I do not succeed will know the reason why- who will not utter any ordinary reproaches but who, because they have been tried and are well versed in what is good and proper and fine as gold, as it were, will say it by the expression on their faces: we helped you and have been a light unto you – we did for you what we could. Did you sincerely desire it? What are our wages and the fruits of our labours? You see, when I think of all that and of so much else, all manner of things – too many to mention, of all the troubles and worries which do not become less as one progresses through life, of suffering, of disappointment, of the danger of failing to a scandalous extent, then that desire is no stranger to me either – I would really like to get away from everything!

And yet – I go on – but with caution and in the hope that I’ll succeed in warding off all these things…”

In Amsterdam he gets acquinted with E. Laurillard, a clergyman who tries to join in the modern ideas. He says: “… the whole creation is God’s music, the notes are sun and clouds, mountain and stream, tree and flower, man and animal. It is one great symphony!”

“That period in Amsterdam, from May, 1877, to 1878, was one long tale of woe. After the first half year Vincent began to lose ardour and courage. Writing exercises and studying grammar was not what he wanted to do; he wanted to comfort and cheer people by bringing them the Gospel – and surely he did not need so much learning for that!” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Vincent failed the exam in July 1878. He then undertook, but failed, a three-month course at the Vlaamsche Opleidingsschool, a Protestant missionary school in Laeken, near Brussels.

The Borinage

“At his own risk Vincent went to the Borinage, where he boarded at 30 francs a month with M. Van der Haegen, Rue de L‘Église 39, at Pâturages near Mons. He taught the children in the evening, visited the poor, and held Bible classes; when the Committee met in January, he would again try to get a nomination. The inter-course with the people pleased him very much, and in his leisure hours he drew large maps of Palestine, of which his father ordered four at 10 francs a piece. At last, in January, 1879, he got a temporary nomination for six months at Wasmes for 50 francs a month, for which he would have to give Bible classes, teach the children, and visit the sick – the work of his heart.

His first letters from there were very contented, and he devoted himself heart and soul to his work, especially the practical part of it; his greatest interest was in nursing the sick and wounded. Soon, however, he fell back into the old exaggerations – he tried to practice the doctrines of Jesus, giving away everything – his money, clothes and bed – leaving the good Denis boardinghouse in Wasmes, and retiring to a miserable hut where every comfort was wanting.

Already his parents had been notified of it, and when, towards the end of February, the Reverend Mr. Rochelieu came for inspection, the bomb exploded. So much zeal was too much for the Committee, and a person who neglected himself so much could not be an example to others. The Church Council at Wasmes held a meeting, and it agreed that if he did not listen to reason, he would lose his position. He himself took it rather coolly. “What shall we do now?” he wrote. &ld Jesus was also very calm in the storm; perhaps it must grow worse before it grows better.” Again his father went to him and succeeded in stilling the storm; he brought him back to the old boardinghouse and advised him to be less exaggerated in his work.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

For some time everything was all right, at least he wrote that there were no complaints. About that time a heavy mine explosion occurred and a strike broke out, so Vincent could devote himself completely to the miners. In her naive religious faith his mother wrote, “Vincent’s letters, which contain so many interesting things, prove that with all his peculiarities, he yet shows a warm interest in the poor; that surely will not remain unobserved by God.

During that same period he also wrote that he had tried to sketch the clothe and tools of the miners and would show them when he came home. In July bad tidings came again. “He does not comply with the wishes of the Committee, and nothing will change him. It seems that he is deaf to all remarks that are made to him,” wrote his mother. When the six months of probation had passed, he was not appointed again, but was given three months to look for another position.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Petit-Wasmes, 26 december 1878

“I’m eagerly longing for a letter from you, to hear again how things are going and how you are, also perhaps to hear if you have recently seen anything beautiful or remarkable.

As far as I’m concerned, you surely understand that there are no paintings here in the Borinage, that in general they haven’t the slightest idea of what a painting is, so it goes without saying that I’ve seen absolutely nothing in the way of art since my departure from Brussels. But this doesn’t mean that this isn’t a very special and very picturesque country, everything speaks, as it were, and is full of character. There was snow these last few days, the dark days before Christmas. Then everything was reminiscent of the medieval paintings by Peasant Bruegel, among others, and by so many others who were so good at expressing the singular effect of red and green, black and white.

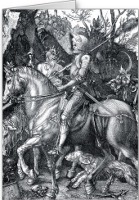

Time and again, what one sees here reminds one of the work of Thijs Maris or Albrecht Dürer, for example.

There are sunken roads here, overgrown with thorn-bushes and with old, twisted trees with their gnarled roots, which look exactly like that road in the etching by Dürer,

The knight and Death.

These last few days, for instance, it was an extraordinary sight, with the white snow in the evening around the twilight hour, seeing the workers returning home from the mines.

These people are completely black when they come out of the dark mines into the daylight again, they look just like chimney-sweeps. Their houses are usually small and had better be called huts, scattered along the sunken roads and in the wood and against the slopes of the hills. One sees moss-covered roofs here and there, and the light shines kindly in the evening through the small-paned windows. “

“His illusion of bringing comfort and cheer into the miserable lives of the miners through the Gospel had gradually been lost in the bitter struggle between doubt and religion which took place within him at that time, and which made him lose his former faith in God. (The Bible texts and religious reflections, which had become more and more rare in his last letters, stopped entirely.)

Nothing else had taken its place yet. He drew and read a great deal – among others Dickens, Beecher Stowe, Victor Hugo, and Michelet – but it was all done without system or purpose. Back in the Borinage he wandered about without work, without friends and very often without bread; for though he received money from home and from Theo, they could not give him more than was strictly necessary, and as it came very irregularly and Vincent was a very poor financier, there were days, even weeks, when he was quite without money.

In October Theo, who had secured a permanent position at Goupil’s in Paris, visited him on his journey thither and tried in vain to induce him to adopt some fixed plan for the future. He was not yet ready to make any decision; before he became conscious of his real power, he was to struggle through the awful winter of 1879-80, that saddest, most hopeless time of his never very fortunate life. (…)

In spring he returned to the vicarage of Etten and spoke again about going to London. “If he really wants to, I shall help him go,” wrote his father. But finally he went back to the Borinage, and that summer of 1880 he lived in the house of the miner Charles Decrucq at Cuesmes. There he wrote in July the wonderfully touching letter (133) which tells what is going on in his innermost self.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Petit-Wasmes, July 1880

“My dear Theo,

It’s with some reluctance that I write to you, not having done so for so long, and that for many a reason. Up to a certain point you’ve become a stranger to me, and I too am one to you, perhaps more than you think; perhaps it would be better for us not to go on in this way.

It’s possible that I wouldn’t even have written to you now if it weren’t that I’m under the obligation, the necessity, of writing to you. If, I say, you yourself hadn’t imposed that necessity. I learned at Etten that you had sent fifty francs for me; well, I accepted them. Certainly reluctantly, certainly with a rather melancholy feeling, but I’m in some sort of impasse or mess; what else can one do?

And so it’s to thank you for it that I’m writing to you.

As you may perhaps know, I’m back in the Borinage; my father spoke to me of staying in the vicinity of Etten instead; I said no, and I believe I acted thus for the best. Without wishing to, I’ve more or less become some sort of impossible and suspect character in the family, in any event, somebody who isn’t trusted, so how, then, could I be useful to anybody in any way?

That’s why, first of all, so I’m inclined to believe, it is beneficial and the best and most reasonable position to take, for me to go away and to remain at a proper distance, as if I didn’t exist. What moulting is to birds, the time when they change their feathers, that’s adversity or misfortune, hard times, for us human beings. One may remain in this period of moulting, one may also come out of it renewed, but it’s not to be done in public, however; it’s scarcely entertaining, it’s not cheerful, so it’s a matter of making oneself scarce. Well, so be it. (…)

I must now bore you with certain abstract things; however, I’d like you to listen to them patiently.

I, for one, am a man of passions, capable of and liable to do rather foolish things for which I sometimes feel rather sorry. I do often find myself speaking or acting somewhat too quickly when it would be better to wait more patiently. I think that other people may also sometimes do similar foolish things. Now that being so, what’s to be done, must one consider oneself a dangerous man, incapable of anything at all? I don’t think so. But it’s a matter of trying by every means to turn even these passions to good account. For example, to name one passion among others, I have a more or less irresistible passion for books, and I have a need continually to educate myself, to study, if you like, precisely as I need to eat my bread. You’ll be able to understand that yourself.

When I was in different surroundings, in surroundings of paintings and works of art, you well know that I then took a violent passion for those surroundings that went as far as enthusiasm. And I don’t repent it, and now, far from the country again, I often feel homesick for the country of paintings. (…)

So you mustn’t think that I’m rejecting this or that; in my unbelief I’m a believer, in a way, and though having changed I am the same, and my torment is none other than this, what could I be good for, couldn’t I serve and be useful in some way, how could I come to know more thoroughly, and go more deeply into any subject? Do you see, it continually torments me, and then one feels a prisoner in penury, excluded from participating in any work, and such and such necessary things are beyond one’s reach.

Because of that, one is not without melancholy, and one feels emptiness where there could be friendship and high and serious affections, and one feels a terrible discouragement gnawing at one’s psychic energy itself, and fate seems able to put a barrier against the instincts for affection, or a tide of revulsion that overcomes one. And then one says How long, O Lord!

Well, then, what can I say; does what goes on inside show on the outside? Someone has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm himself at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke at the top of the chimney and then go on their way. So now what are we to do, keep this fire alive inside, have salt in ourselves, wait patiently, but with how much impatience, await the hour, I say, when whoever wants to, will come and sit down there, will stay there, for all I know? May whoever believes in God await the hour, which will come sooner or later. (…)

I’m writing you somewhat at random whatever comes to my pen; I would be very happy if you could somehow see in me something other than some sort of idler.

Because there are idlers and idlers, who form a contrast.

There’s the one who’s an idler through laziness and weakness of character, through the baseness of his nature; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one. Then there’s the other idler, the idler truly despite himself, who is gnawed inwardly by a great desire for action, who does nothing because he finds it impossible to do anything since he’s imprisoned in something, so to speak, because he doesn’t have what he would need to be productive, because the inevitability of circumstances is reducing him to this point.

Such a person doesn’t always know himself what he could do, but he feels by instinct, I’m good for something, even so! I feel I have a raison d’être! I know that I could be quite a different man! For what then could I be of use, for what could I serve! There’s something within me, so what is it! That’s an entirely different idler; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one.

In the springtime a bird in a cage knows very well that there’s something he’d be good for; he feels very clearly that there’s something to be done but he can’t do it; what it is he can’t clearly remember, and he has vague ideas and says to himself, ‘the others are building their nests and making their little ones and raising the brood’, and he bangs his head against the bars of his cage. And then the cage stays there and the bird is mad with suffering.

‘Look, there’s an idler’, says another passing bird — that fellow’s a sort of man of leisure. And yet the prisoner lives and doesn’t die; nothing of what’s going on within shows outside, he’s in good health, he’s rather cheerful in the sunshine. But then comes the season of migration. A bout of melancholy — but, say the children who look after him, he’s got everything that he needs in his cage, after all — but he looks at the sky outside, heavy with storm clouds, and within himself feels a rebellion against fate. I’m in a cage, I’m in a cage, and so I lack for nothing, you fools! Me, I have everything I need! Ah, for pity’s sake, freedom, to be a bird like other birds!

An idle man like that resembles an idle bird like that.

And it’s often impossible for men to do anything, prisoners in I don’t know what kind of horrible, horrible, very horrible cage. There is also, I know, release, belated release. A reputation ruined rightly or wrongly, poverty, inevitability of circumstances, misfortune; that creates prisoners.

You may not always be able to say what it is that confines, that immures, that seems to bury, and yet you feel I know not what bars, I know not what gates — walls.

Is all that imaginary, a fantasy? I don’t think so; and then you ask yourself, Dear God, is this for long, is this for ever, is this for eternity?

You know, what makes the prison disappear is every deep, serious attachment. To be friends, to be brothers, to love; that opens the prison through sovereign power, through a most powerful spell. But he who doesn’t have that remains in death. But where sympathy springs up again, life springs up again….”

Vincent was at his wit’s end; his family did not know which advice to give him. Eventually Theo gave him the idea of training to become an artist. Vincent’s initial reaction to this idea was incomprehension. Some years later he wrote to Theo: “I remember quite well, now that you wrote about it, that at the time when you spoke of my becoming a painter, I thought it very impractical and would not hear of it.”

“Now, in the days of deepest discouragement and darkness, at last the light began to dawn. Not in books would he find satisfaction, nor find his work in literature, as his letters sometimes suggested; he turned back to his old love, “I said to myself…I will take up my pencil…I will go on with my drawing. From that moment everything has seemed transformed for me…” It sounds like a cry of deliverance, and once more, “…do not fear for me. If I can only continue to work…it will set me right again.” At last he had found his work, and his mental equilibrium was restored; he no longer doubted himself, and however difficult or hard his life became, the inner serenity, the conviction of having found his proper calling, never deserted him again.

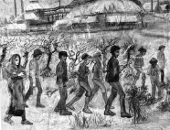

The little room in the house of the miner Decrucq, which he had to share with the children, was his first studio. There he began his painter’s career with the first original drawings of miners going to work in the early morning. There he copied with restless activity the large drawings after Millet, and when the room got too narrow for him, he took his work out into the garden.

(…)

It was during these days that he undertook, with 10 francs in his pocket, the hopeless expedition to Courrières, the dwelling place of Jules Breton, whose pictures and poems he so much admired, and with whom he secretly hoped to come into contact in some way or other.” (Jo van Gogh-Bonger)

Cuesmes, 24 Sept. 1880

“Dear Theo,

Your letter did me good; I thank you for writing to me like that. (…)

What you say in your letter on the subject of Barbizon is very true and I’ll tell you one or two things that will prove to you that that’s my own way of seeing as well. I haven’t seen Barbizon, but although I haven’t seen it, last winter I saw Courrières. I made a trip on foot mainly in the Pas de Calais, not the Channel but the department. Or province.

I made that trip hoping perhaps to find work there (any sort, if possible; I would have accepted anything), but actually without any real plan, I couldn’t precisely say why. But I’d said to myself, You must see Courrières. I had only 10 francs in my pocket, and having started out by taking the train I’d soon exhausted those resources, and having stayed on the road for a week, I trudged rather painfully. Nevertheless, I saw Courrières and the outside of Mr Jules Breton’s studio. The outside of this studio disappointed me a little, seeing that it’s a brand-new studio and newly built in brick, of a Methodist regularity (…)

I didn’t dare to introduce myself, so as to go in. (…)

But at any rate I saw the Courrières countryside then, the haystacks, the brown farmland or the almost coffee-coloured marly soil, with whitish spots where the marl appears, which is something rather extraordinary for those of us who are used to blackish soil. And the French sky seemed to me far more clear and limpid than the smoky and misty Borinage sky.

Furthermore, there were the farmhouses and sheds that had still preserved their mossy thatched roofs, God be praised and thanked for it; I also saw hosts of crows, famous from the paintings of Daubigny and Millet. Not to mention first of all, as one should, the typical and picturesque figures of the workmen: different diggers, woodcutters, a farm-hand driving his team, and the occasional outline of a woman in a white bonnet.

(…)

I earned a few crusts of bread en route here and there in exchange for some drawings that I had in my suitcase. But when my ten francs were gone, I had to bivouac out in the open for the last 3 nights, once in an abandoned carriage, all white with frost in the morning, a rather poor shelter, once in a wood-pile and once, and it was a little better, in a haystack that had been breached, where I managed to make a slightly more comfortable nest, only a fine rain didn’t exactly add to my well-being.

Well, and notwithstanding, it was in this extreme poverty that I felt my energy return and that I said to myself, in any event I’ll recover from it, I’ll pick up my pencil that I put down in my great discouragement and I’ll get back to drawing, and from then on, it seems to me, everything has changed for me, and now I’m on my way and my pencil has become somewhat obedient and seems to become more so day by day.”

In October 1880 Vincent moved to Brussels. There he was in a really stimulating environment. The refined artist Willem Roelofs gave him good advice, and with the young artist Anthon van Rappard he could share his enthousiasm. The two became firm friends.

“During this time in Brussels Van Gogh tried to make drawings with more character, but he did not altogether succeed. (…) One surprising highlight from this period is pen-and-ink drawing

The bearers of the burden

in which the labouring figures with their sacksof of pit coal are quite successfully executed, while the composition of the partly industrial landscape is excellent.” (Van Heugten)