Drenthe · Mar 23, 01:36 AM by Ad van den Ende

At first Vincent did not like Drenthe. He lodged in an inn in Hoogeveen.

There he had a simple attic room. He missed having a studio, and he was plagued by a lack of materials. People laughed at him and he was ridiculed because of his Brabant dialect. They refused to model for him.

To Theo van Gogh. Hoogeveen, on or about Friday, 21 September 1883.

“(…)

I have a few studies of the heath, which I’ll send you when they’re thoroughly dry, and have also begun watercolours. And I’ve also started pen drawings again, specifically with a view to painting, because one can go into such details with the pen as painted studies cannot do, and one does well to make two studies, one entirely drawn for the way things are put together, and one painted for the colour. If this can be done, that is, and the occasion permits, this is a way of working up the painted study later.”

To Theo van Gogh. Hoogeveen, on or about Wednesday, 26 September 1883

(…)

I’m at a point where I need credit, trust and some warmth, and you see there’s no trust in me. You’re an exception to this, but precisely because everything falls on you it makes it even more apparent how dismal everything is in my case.

And if I look at my things, they’re too poor, too inadequate, too much exhausted. We’re having gloomy, rainy days here, and when I come into the corner of the attic where I’ve installed myself it’s all remarkably melancholy there — with the light from one single glass roof tile that falls on an empty painting box, on a bundle of brushes with few decent bristles remaining, well it’s socuriously melancholy that luckily it also has a funny enough side not to weep over it but to regard it more cheerfully. But even so, it’s in a very strange relationship to my plans — in a very strange relationship to the seriousness of the work, and — this is where the laughing stops.”

To Theo van Gogh. Nieuw-Amsterdam, on or about Wednesday, 3 October 1883

“The heath was extraordinarily beautiful this evening. There’s a Daubigny in one of the Albums Boetzel that expresses that effect precisely. The sky was an inexpressibly delicate lilac white — not fleecy clouds, because they were more joined together and covered the whole sky, but tufts in tints more or less of lilac — grey — white — a single small rent through which the blue gleamed. Then on the horizon a sparkling red streak — beneath it the surprisingly dark expanse of brown heath, and a multitude of low roofs of small huts standing out against the glowing red streak.

In the evening this heath often has effects that the English would describe as weird and quaint. The spiky silhouettes of Don Quixote-like mills or strange hulks of drawbridges are profiled against the teeming evening sky. In the evening a village like that is sometimes really snug, with the light from the little windows reflected in the water or in mud and puddles.

Before I left Hoogeveen I painted a few more studies there, among them a large farmhouse with a mossy roof.

(…)

How I wish that we could walk together here and — paint together. I believe that the countryside would win you over and convince you. Adieu, I hope that you’re well and will have a bit of good fortune. I thought about you again and again on this trip. With a handshake. Ever yours,

Vincent“

To Theo van Gogh. Nieuw-Amsterdam, on or about Sunday, 7 October 1883

“Yesterday I drew decaying oak roots, so-called bog trunks (being oak trees that have been buried under the peat for perhaps a century, over which new peat has formed — when the peat is dug out these bog trunks come to light).1

These roots lay in a pool in black mud. A few black ones lay in the water, in which they were reflected, a few bleached ones on the black plain. A little white track ran alongside it, behind it more peat, black as soot. Then a stormy sky overhead. That pool in the mud with those decaying roots, it was absolutely melancholy and dramatic, just like Ruisdael, just like Jules Dupré.”

To Theo van Gogh. Nieuw-Amsterdam, on or about Tuesday, 16 October 1883

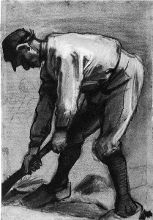

“Today I walked behind the ploughmen who were ploughing up a potato field, and women walking behind them picking up a few potatoes that were left.”

To Theo van Gogh. Nieuw-Amsterdam, Sunday, 28 October 1883

(…)

If something within yourself says ‘you aren’t a painter’ — IT’S THEN THAT YOU SHOULD PAINT, old chap, and that voice will be silenced too, but precisely because of that. (…)

One must take it up with assurance, with a conviction that one is doing something reasonable, like the peasant guiding his plough or like our friend in the skatch, who is doing his own harrowing. If one has no horse, one is one’s own horse .”

But Theo refused coming to Drenthe and becoming a painter. If he had done so, they would have had both no income.

Vincent was brightened up by a trip to Zweeloo.

To Theo van Gogh. Nieuw-Amsterdam, Friday, 2 November 1883.

“Dear brother,

Just wanted to tell you about a trip to Zweeloo(…)

Imagine a trip across the heath at 3 o’clock in the morning in an open cart (I went with the man where I lodge, who had to go to the market in Assen). Along a road, or ‘diek’ as they say here, which they’d put mud on to raise it instead of sand. It was much nicer even than the barge. When it was only just starting to get a little lighter and the cocks were crowing everywhere by the huts scattered over the heath, the few cottages we passed — surrounded by slender poplars whose yellow leaves one could hear falling — an old squat tower in a little churchyard with earth bank and beech hedge, the flat landscapes of heath or wheatfields, everything, everything became just exactly like the most beautiful Corots. A silence, a mystery, a peace as only he has painted.

It was still very dark, though, when we got to Zweeloo at 6 o’clock in the morning — I saw the real Corots even earlier in the morning. The ride into the village was really so beautiful. Huge mossy roofs on houses, barns, sheepfolds, sheds.

(…)

I didn’t find a single painter in Zweeloo, though, and the people said they never come there in winter. It’s precisely in winter that I hope to be there. Since there were no painters, I decided to walk back and do some drawing on the way instead of waiting for my landlord’s return.

So I started to make a sketch of the very apple orchard where Liebermann made his large painting. And then back along the road we had driven down early on. At the moment that area around Zweeloo is entirely given over to young wheat — vast, sometimes, that most tender of tender greens that I know. With above it a sky of a delicate lilac white that gives an effect — I don’t think it can be painted, but for me it’s the basic tone that one must know in order to know what the basis of other effects is.

A black earth, flat — infinite — a clear sky of delicate lilac white. That earth brings forth that young wheat — it’s as if that wheat is a growth of mould. That’s what the good, fertile fields of Drenthe are, au fond — everything in a vaporous atmosphere. Think of the Last day of creation by Brion — well, yesterday I felt that I understood the meaning of that painting.

The poor soil of Drenthe is the same, only the black earth is even blacker — like soot — not a lilac black like the furrows, and melancholically overgrown with eternally rotting heather and peat. I see that everywhere — the chance effects on that infinite background: in the peat bogs the sod huts, in the fertile areas, really

primitive hulks of farmhouses and sheepfolds with low, very low walls, and huge mossy roofs. Oaks around them. When one travels for hours and hours through the region, one feels as if there’s actually nothing but that infinite earth, that mould of wheat or heather, that infinite sky. Horses, people seem as small as fleas then. One feels nothing any more, however big it may be in itself, one only knows that there is land and sky.

However, in one’s capacity as a tiny speck watching other tiny specks — leaving aside the infinite — one discovers that every tiny speck is a Millet. I passed a little old church, just exactly, just exactly the church at Gréville in Millet’s little painting in the Luxembourg; but here, instead of the little peasant with the spade in that painting, a shepherd with a flock of sheep came along the hedge. One didn’t see through to the sea in the background but only to the sea of young wheat, the sea of furrows instead of that of the waves. The effect produced: the same. I saw ploughmen, very busy now, a sand-cart, shepherds, road workers, dung-carts. In a little inn along the way drew a little old woman at the spinning wheel, little dark silhouette — like something out of a fairy tale — little dark silhouette against a bright window through which one saw the bright sky and a path through the delicate green and a few geese cropping the grass.

And then, when dusk fell — imagine the silence, the peace of that moment! Imagine, right then, an avenue of tall poplars with the autumn leaves, imagine a broad muddy road, all black mud with the endless heath on the right, the endless heath on the left, a few black, triangular silhouettes of hovels, with the red glow of the fire shining through the tiny windows, with a few pools of dirty, yellowish water that reflect the sky, where bogwood trunks lie rotting. Imagine this muddy mess in the evening twilight with a whitish sky above, so everything black on white. And in this muddy mess a rough figure — the shepherd — a throng of oval masses, half wool, half mud, that bump into one another, jostle one another — the flock. You see it coming — you stand in the midst of it — you turn round and follow them.

With difficulty and reluctantly they progress along the muddy road. Still, there’s the farm in the distance — a few mossy roofs and piles of straw and peat between the poplars. Again the sheepfold is like a triangle in silhouette.

The door stands wide open like the entrance to a dark cave. The light from the sky behind shines through the cracks in the boards at the back. The whole caravan of masses of wool and mud disappears into this cave — the shepherd and a woman with a lantern shut the doors behind them.

That return of the flock in the dusk was the finale of the symphony that I heard yesterday. That day passed like a dream, I had been so immersed in that heart-rending music all day that I had literally forgotten even to eat and drink — I took a slice of coarse peasant bread and a cup of coffee at the little inn where I drew the spinning wheel. The day was over, and from dawn to dusk, or rather from one night to the other night, I had forgotten myself in that symphony.“

After only three months Vincent left Drenthe. He went to Nuenen, where his father had been installed as a pastor.

Op dit artikel kan niet gereageerd worden.