Paris (March 1886– February 1888) · 3888 dagen geleden by Ad van den Ende

Paris (Claude Monet)

MARCH

Vincent traveled to Paris, where he shared Theo’s Rue Laval apartment on Montmartre. Theo kept a stock of Impressionist paintings in his gallery on Boulevard Montmartre (by artists including Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro).

APRIL – MAY

Vincent worked at Cormon’s studio.

Torso, done at Cormon’s studio

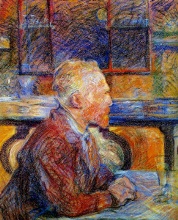

There he met fellow students like Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who painted a portrait of Van Gogh with pastel.

Portrait of Vincent van Gogh from Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Conflicts arose between the brothers. At the end of 1886, Theo found that living with Vincent was “almost unbearable”. By the spring of 1887, they were again at peace.

In Asnières Vincent became acquainted with Signac. With Émile Bernard, he adopted elements of Pointillism,

Harbor Signac

a technique in which a multitude of small colored dots are applied to the canvas such that—when seen from a distance—they create an optical blend of hues.

The style stresses the value of complementary colours—including blue and orange—to form vibrant contrasts that are enhanced when juxtaposed. While in Asnières, he painted parks and restaurants and the Seine, including .Bridges across the Seine at Asnieres.

Bridges across the Seine at Asnières

In November 1887, Theo and Vincent met and befriended Paul Gauguin, who had just arrived in Paris.

Towards the end of the year, Vincent arranged an exhibition of paintings by himself, Bernard, Anquetin, and probably Toulouse-Lautrec in the Grand-Bouillon Restaurant du Chalet.

Grand-Bouillon Restaurant du Chalet.

In a contemporary account, Émile Bernard wrote of the event: “On the avenue de Clichy a new restaurant was opened. Vincent used to eat there. He proposed to the manager that an exhibition be held there …. Canvases by Anquetin, by Lautrec, by Koning…filled the hall….It really had the impact of something new; it was more modern than anything that was made in Paris at that moment.”

Self-portrait

In Paris his outward appearance underwent a change. He had improved his appearance and found the mirror a pleasant thing. He painted many selfportraits.

To Horace Mann Livens, Paris, September or October 1886.

My dear Mr Livens,

Since I am here in Paris I have very often thought of your self and work. You will remember that I liked your colour, your ideas on art and litterature and I add, most of all, your personality.

I have already before now thought that I ought to let you know what I was doing, where I was.

But what refrained me was that I find living in Paris is much dearer than in Antwerp and not knowing what your circumstances are I dare not say Come over to Paris, without warning you that it costs one dearer than Antwerp and that if poor, one has to suffer many things. As you may imagine. But on the other hand there is more chance of selling.

There is also a good chance of exchanging pictures with other artists.

In one word, with much energy, with a sincere personal feeling of colour in nature I would say an artist can get on here notwithstanding the many obstructions. And I intend remaining here still longer.

There is much to be seen here – for instance Delacroix to name only one master.

In Antwerp I did not even know what the Impressionists were, now I have seen them and though not being one of the club, yet I have much admired certain Impressionist pictures – degas, nude figure – Claude Monet, landscape.

Claude Monet, Landscape.

And now for what regards what I myself have been doing, I have lacked money for paying models, else I had entirely given myself to figure painting but I have made a series of colour studies in painting simply flowers, red poppies, blue corn flowers and myosotis. White and rose roses, yellow chrysanthemums – seeking oppositions of blue with orange, red and green, yellow and violet, seeking THE BROKEN AND NEUTRAL TONES to harmonise brutal extremes.

Trying to render intense COLOUR and not a grey harmony.

Vase with Poppies, Cornflowers, Peonies and Chrysanthemums.

Now after these gymnastics I lately did two heads which I dare say are better in light and colour than those I did before.

So as we said at the time in COLOUR seeking life, the true drawing is modelling with colour.

I did a dozen landscapes too, frankly green, frankly blue.

And so I am struggling for life and progress in art.

Now I would very much like to know what you are doing and whether you ever think of going to Paris.

If ever you did come here, write to me before and I will, if you like, share my lodgings and studio with you so long as I have any. In spring – say February or even sooner – I may be going to the south of France, the land of the blue tones and gay colours.

And look here, if I knew you had longings for the same we might combine. I felt sure at the time that you are a thorough colourist and since I saw the Impressionists I assure you that neither your colour nor mine as it is developing itself, is exactly the same as their theories but so much dare I say, we have a chance and a good one of finding friends.

I hope your health is all right. I was rather low down in health when in Antwerp but got better here.

Write to me, in any case remember me to Allan, Briët, Rink, Durand, but I have not so often thought on any of them as I did think of you – almost daily.

Shaking hands cordially.

Yours truly,

Vincent

What regards my chances of sale, look here, they are certainly not much but still I do have a beginning.

At this present moment I have found four dealers who have exhibited studies of mine. And I have exchanged studies with several artists.

Now the prices are 50 francs. Certainly not much but – as far as I can see one must sell cheap to rise, and even at costing price. And mind my dear fellow, Paris is Paris, there is but one Paris and however hard living may be here and if it became worse and harder even – the french air clears up the brain and does one good – a world of good.

Le Moulin de la Galette on Montmartre

I have been in Cormons studio for three or four months but did not find that as useful as I had expected it to be. It may be my fault however, any how I left there too as I left Antwerp and since I worked alone, and fancy that since I feel my own self more.

Trade is slow here, the great dealers sell Millet, Delacroix, Corot, Daubigny, Dupré, a few other masters at exorbitant prices. They do little or nothing for young artists. The second class dealers contrariwise sell those but at very low prices. If I asked more I would do nothing, I fancy. However I have faith in colour, even what regards the price the public will pay for it in the longer run.

But for the present things are awfully hard, therefore let anyone who risks to go over here consider there is no laying on roses at all.

What is to be gained is progress and, what the deuce, that it is to be found here I dare ascertain. Anyone who has a solid position elsewhere, let him stay where he is but for adventurers as myself I think they lose nothing in risking more. Especially as in my case I am not an adventurer by choice but by fate and feeling nowhere so much myself a stranger as in my family and country.

Kindly remember me to your landlady Mrs Roosmaelen and say her that if she will exhibit something of my work I will send her a small picture of mine.”

Terrace in the Jardin du Luxembourg

We see people out for a stroll on a summer’s day. The scene is flooded with bright sunlight. Even the woman in black (on the left) is carrying a cheerful red parasol. Vincent has gladly acquiesced in the visual stimuli of the scene. In this Jardin du Luxenbourg scene Vincent created one of his most attractive ‘realistic’ paintings

To Theo van Gogh. Paris, between about Saturday, 23 and about Monday, 25 July 1887.

My dear friend,

I thank you for your letter and for what it contained.

I feel sad that even if successful, painting won’t bring in what it costs.

I was touched by what you wrote about home – ‘they’re doing quite well, but it’s sad to see them nevertheless’. But a dozen years ago or so one would have sworn that the family would continue to prosper after all, and that things would work out well. It would please our mother greatly if your marriage came off, and for your health and business affairs you shouldn’t remain single anyway.

Myself — I feel I’m losing the desire for marriage and children, and at times I’m quite melancholy to be like that at 35 when I ought to feel quite differently. And sometimes I blame this damned painting.

It was Richepin who said somewhere: the love of art makes us lose real love.

Self-portrait

I find that terribly true, but on the other hand real love puts you right off art.

And sometimes I already feel old and broken, but still sufficiently in love to stop me being enthusiastic about painting.

To succeed you have to have ambition, and ambition seems absurd to me. I don’t know what will come of it. Most of all, I’d like to be less of a burden to you — and that’s not impossible from now on. Because I hope to make progress in such a way that you’ll be able to show what I’m doing, with confidence, without compromising yourself.

And then I’m going to retreat to somewhere in the south so as not to see so many painters who repel me as men. (…)

I saw Tanguy yesterday and he put a canvas I had just done in his window, I’ve done four since you left, and I have a big one on the go. I’m well aware that these big, long canvases are hard to sell, but in time people will see that there’s open air and good cheer in them. Now the whole lot will make a decoration for a dining room or a house in the country.

And if you really fell in love and then got married, I wouldn’t think it impossible that you too might manage to get hold of a house in the country, like so many other picture dealers. If you live well you spend more, but you also gain more ground, and perhaps these days we do better if we look rich than if we look hard up. It’s better to have fun than to kill yourself. Warm regards to all at home.

Yours truly,

Vincent

View of Montmartre with Windmills

The three mills on Monmartre reminded Vincent of his homeland. He tries to capture the texture and consistency of things. “Van Gogh’s ‘realisme’ peaked in his first Paris phase. And it was only because he had grown confident of his command that he was able to shrug off virtuoso technique in the way he did in the years ahead.

He made the greatest leap in his use of colour.” (Walther & Metzger)

Vincent’s entire attention was on colour. He painted over forty flower still lifes.

Still-life with Decanter and Lemon on a Plate

Theo wrote to their mother: “He is far more open-minded than he used to be. and very popular. For example: he has acquaintances who send him a fine bunch of flowers to paint every week, His main reason for painting flowers is that he wants to freshen his colours for later work.”

Vincent learned the power of tones. He painted that which he saw. He was still faithful to realism.

To Willemien van Gogh. Paris, late October 1887.

My dear little sister,

(…)

For my part, I’m always glad that I’ve read the Bible better than many people nowadays, just because it gives me a certain peace that there have been such lofty ideas in the past. But precisely because I think the old is good, I find the new all the more so. All the more so because we can take action ourselves in our own age, and both the past and the future affect us only indirectly.

Self-portrait

My own fortunes dictate above all that I’m making rapid progress in growing up into a little old man, you know, with wrinkles, with a bristly beard, with a number of false teeth &c.

But what does that matter? I have a dirty and difficult occupation, painting, and if I weren’t as I am I wouldn’t paint, but being as I am I often work with pleasure, and I see the possibility glimmering through of making paintings in which there’s some youth and freshness, although my own youth is one of those things I’ve lost.

If I didn’t have Theo it wouldn’t be possible for me to do justice to my work, but because I have him as a friend I believe that I’ll make more progress and that things will run their course. It’s my plan to go to the south for a while, as soon as I can, where there’s even more colour and even more sun.

But what I hope to achieve is to paint a good portrait. Anyway.

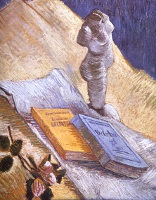

Still Life with Plaster, two Novels and a Rose

It would please me if you would write and tell me how Margot Begemann is doing and how they’re doing at De Groot’s. How did that business turn out? Did Sien de Groot marry her cousin? And did her child live?

What I think about my own work is that the painting of the peasants eating potatoes that I did in Nuenen is after all the best thing I did. Only since then I haven’t had the opportunity to find models, but on the contrary have had the opportunity to study the question of colour. And if I do find models for my figures again later, then I hope to show that I’m looking for something other than little green landscapes or flowers.

Last year I painted almost nothing but flowers to accustom myself to a colour other than grey, that’s to say pink, soft or bright green, light blue, violet, yellow, orange, fine red. And when I painted landscape in Asnières this summer I saw more colour in it than before.

Fishing in the Spring, Pont de Clichy

I’m studying this now in portraits. And I have to tell you that I’m painting none the worse for it, perhaps because I could tell you very many bad things about both painters and paintings if I wanted to, just as easily as I could tell you good things about them.

Agostina Segatori, sitting in the café du Tambourin

I don’t want to be one of the melancholics or those who become sour and bitter and morbid. To understand all is to forgive all, and I believe that if we knew everything we’d arrive at a certain serenity. Now having this serenity as much as possible, even when one knows — little — nothing — for certain, is perhaps a better remedy against all ills than what’s sold in the chemist’s. A lot comes of its own accord, one grows and develops of one’s own accord.

(…)

At any rate I can do something about painting personally, but as far as writing’s concerned I’m not in the business. Anyway, it’s not a bad idea for you to want to become an artist, because if one has fire in one, and soul, one can’t keep stifling them and — one would rather burn than suffocate. What’s inside must get out. Me, for instance, it gives me air when I make a painting, and without that I’d be unhappier than I am. Give Ma my very warmest regards.

Vincent

Self-portrait with Straw Hat

And there are times when it’s by no means clear to us that art should be something sacred or good.

Anyway, think carefully about whether it isn’t better, if one has a feeling for art and wants to work in it, to say that one is doing it because one was created with that feeling and can’t do anything else and is following one’s nature, than to say one is doing it for a good cause.

Does it not say in A la recherche du bonheur that evil lies in our own natures — which we didn’t create ourselves?

What I think is so good about the moderns is that they don’t moralize like the old ones.

It seems coarse to many people, for instance, and they’re angered by it: vice and virtue are chemical products like sugar and vitriol.”

1887: A Turning Point

Three Pairs of Shoes

These shoes are the ‘trademark’ of an artist who has travelled a long distance. Vincent has painted them exactly as he saw them.

A Pair of Shoes

Neither these shoes are fashionable foot-wear. But they have a warmer orange tint and they are seen against the blue background. The white dots (the hobnails) also have a purely aesthetic function. This painting was done in 1887. The other probably dated from summer 1886. “The two still lifes of shoes define the 1887 watershed: Van Gogh was questioning his previous use of local colour and his purely descriptive style.(…) The Self-Portrait with Straw Hat, done in summer 1887, similarly departs from the approach of earlier work. Now it is colour analogy that engages the painters main”interest…” (Walther&Metsger)

Self-Portrait with Straw Hat

To Emile Bernard. Paris, about December 1887.

My dear old Bernard,

I feel the need to beg your pardon for leaving you so abruptly the other day. Which I therefore do herewith, without delay. I recommend that you read Tolstoy’s Les Légendes Russes, and I’ll also let you have the article on E. Delacroix that I’ve spoken to you about.

I, for my part, did go to Guillaumin’s anyway, but in the evening, and I thought that perhaps you didn’t know his address, which is 13 quai d’Anjou. I believe that, as a man, Guillaumin has sounder ideas than the others, and that if we were all like him we’d produce more good things and would have less time and inclination to be at each other’s throats.

Chestnut Tree in Blossom

I persist in believing that — not because I gave you a piece of my mind but because it will become your own conviction — I persist in believing that you’ll realize that in the studios not only does one not learn very much as far as painting goes, but not much that’s good in terms of savoir vivre, either. And that one finds oneself obliged to learn to live, as one does to paint, without resorting to the old tricks and trompe l’oeil of schemers.

I don’t think your portrait of yourself will be your last, or your best— although all in all it’s frightfully you.

Look here — briefly, what I was trying to explain to you the other day comes down to this. In order to avoid generalities, let me take an example from life.

If you’ve fallen out with a painter, with Signac, for example, and if as a result you say: if Signac exhibits where I exhibit, I’ll withdraw my canvases — and if you run him down, then it seems to me that you’re not behaving as well as you could behave.

Because it’s better to take a long look at it before judging so categorically, and to reflect, reflection making us see in ourselves, when there’s a falling out, as many faults on our own side as in our adversary, and in him as many justifications as we might desire for ourselves.

If, therefore, you’ve already considered that Signac and the others who are doing pointillism often make very beautiful things with it —

Instead of running those things down, one should respect them and speak of them sympathetically, especially when there’s a falling out.

Wheatfield with a Lark

Otherwise one becomes a narrow sectarian oneself, and the equivalent of those who think nothing of others and believe themselves to be the only righteous ones.

This extends even to the academic painters, because take, for example, a painting by Fantin-Latour — and above all his entire oeuvre. Well then — there’s someone who hasn’t rebelled, and does that prevent him, that indefinable calm and righteousness that he has, from being one of the most independent characters in existence?

I also wanted to say a word to you about the military service that you’ll be required to do. You must absolutely see to that now.

Directly, in order to inform yourself properly about what one can do in such an event; first to retain the right to work, to be able to choose a garrison, &c. But indirectly, by taking care of your health. You mustn’t arrive there too anaemic or too agitated if you want to emerge from it stronger.

I don’t see it as a very great misfortune for you that you have to join the army, but as a very grave ordeal, from which, if you emerge from it, you’ll emerge a very great artist. Until then, do all you can to build yourself up, because you’ll need quite a bit of spirit. If you work hard that year, I believe that you may well succeed in having a fair stock of canvases, some of which we’ll try to sell for you, knowing that you’ll need pocket money to pay for models.

I’ll gladly do all I can to make a success of what was started in the dining-room, but I believe that the first condition for success is to put aside petty jealousies; it’s only unity that makes strength. It’s well worth sacrificing selfishness, the ‘each man for himself’, in the common interest.

I shake your hand firmly.

Vincent

To Paul Gauguin. Arles, Monday, 21 January 1889.

You talk to me in your letter about a canvas of mine, the sunflowers with a yellow background3 — to say that it would give you some pleasure to receive it. I don’t think that you’ve made a bad choice – if Jeannin has the peony, Quost the hollyhock, I indeed, before others, have taken the sunflower.

Two cut Sunflowers

Influence of Japanese art on Van Gogh

The great Wave of Kanagawa

“Japonaiserie” was the term Vincent used to express the influence of Japanese art.

Before 1854 trade with Japan was confined to a Dutch monopoly and Japanese goods imported into Europe were for the most part confined to porcelain and lacquer ware. The Convention of Kanagawa put an end to the 200 year old Japanese foreign policy of Seclusion and opened up trade between Japan and the West.

Van Gogh’s interest in Japanese ukiyo-e prints dates from his time in Antwerp when he was also interesting himself in Delacroix’s theory of colour and where he used them to decorate his studio.

The storm on the Lake of Genesareth Delacroix

One of De Goncourt’s sayings was ‘Japonaiserie for ever’. “Well, these docks [at Antwerp] are one huge Japonaiserie, fantastic, singular, strange … I mean, the figures there are always in motion, one sees them in the most peculiar settings, everything fantastic, and interesting contrasts keep appearing of their own accord.”

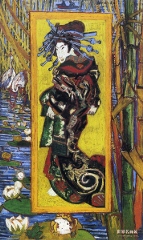

During his subsequent stay in Paris, where Japonisme had become a fashion influencing the work of the Impressionists, he began to collect ukiyo-e prints and eventually to deal in them with his brother Theo. At that time he made three copies of ukiyo-e prints, The Courtesan and the two studies after Hiroshige.

The Courtesan

Artists such as Manet, Degas and Monet, followed by Van Gogh, began to collect the cheap colour wood-block prints called ukiyo-e prints. For a while Vincent and his brother Theo dealt in these prints and they eventually amassed hundreds of them.

During his stay in Paris, he collected more Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints; he became interested in such works when, in 1885, in Antwerp he used them to decorate the walls of his studio.

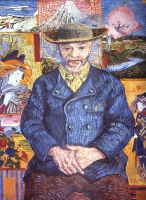

Portrait of Père Tanguy

“Japanese prints acted as a catalyst for Van Gogh: he succeeded brilliantly in fusing their abstract and decorative qualities with his own vision, which was grounded in realism and observation.” (Ann Dumas)

Italian Woman (Agostina Segatori ?)

Vincent collected hundreds of prints, which are visible in the backgrounds of several of his paintings. In his 1887 ,Portrait of Père Tanguy several can be seen hanging on the wall behind the main figure.

His 1888 Plum Tree in Blossom (After Hiroshige) is a vivid example of the admiration he had for the prints he collected. His version is slightly bolder than Hiroshige’s original.

Plum Tree in Blossom (After Hiroshige)

In a letter to Theo dated about 5 June 1888 Vincent remarks

About staying in the south, even if it’s more expensive — Look, we love Japanese painting, we’ve experienced its influence — all the Impressionists have that in common — [so why not go to Japan], in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all.

A month later he wrote: “All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art…”

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake (1857) by Hiroshige

Japanese Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) (1887) by Vincent Van Gogh

Characteristic features of ukiyo-e woodprints include their ordinary subject matter, the distinctive cropping of their compositions, bold and assertive outlines, absent or unusual perspective, flat regions of uniform colour, uniform lighting, absence of chiaroscuro, and their emphasis on decorative patterns. One or more of these features can be found in numbers of Vincent’s paintings from his Antwerp period onwards.

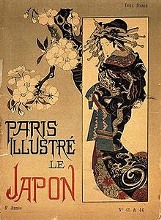

Title page of Paris Illustré “Le Japon’ vol. 4, May 1886

The May 1886 edition of Paris Illustré was devoted to Japan with text by Tadamasa Hayashi who may have inspired van Gogh’s utopian notion of the Japanese artist:

“Just think of that; isn’t it almost a new religion that these Japanese teach us, who are so simple and live in nature as if they themselves were flowers?”

“And we wouldn’t be able to study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much happier and more cheerful, and it makes us return to nature, despite our education and our work in a world of convention.”

The cover carried a reverse image of a colour woodblock by Keisai Eisen depicting a Japanese courtesan or Oiran.

Finally, in February 1888, feeling worn out from life in Paris, Vincent left, having painted over 200 paintings during his two years in the city. Only hours before his departure, accompanied by Theo, he paid his first and only visit to Seurat in his atelier.”

Vincent developed an idealised conception of the Japanese artist which led him to the Yellow House at Arles and his attempt to form a utopian art colony there with Paul Gauguin.

Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel

“The last self-portrait Van Gogh made in Paris, this work is the monumental result of self-examination, painted in bright, unmixed, complementary colours. (…) in the space of only two years van Gogh had mastered the Impressionists’ palette and colour theory.” (Aukje Vergeest)