Nuenen: the weavers · 3917 dagen geleden by Ad van den Ende

1883

DECEMBER

Vincent moves to Nuenen in the southern Netherlands. His parents live there now.

They try to overlook his negligent dress style and his unusual behaviour.

Vincent stays till november 1885 in Nuenen. There he produes almost two hundred paintings and numerous drawings and watercolours. He uses dark, earthy colours. His work is expressive.

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Saturday, 15 December 1883.

Dear brother,

I feel what Pa and Ma instinctively think about me (I don’t say reasonably).

There’s a similar reluctance about taking me into the house as there would be about having a large, shaggy dog in the house. He’ll come into the room with wet paws — and then, he’s so shaggy. He’ll get in everyone’s way. And he barks so loudly.

In short — it’s a dirty animal.

Very well — but the animal has a human history and, although it’s a dog, a human soul, and one with finer feelings at that, able to feel what people think about him, which an ordinary dog can’t do.

And I, admitting that I am a sort of dog, accept them as they are.

This home is also too good for me, and Pa and Ma and the family are so unduly fine (no feelings, though) and — and — they are ministers — many ministers.

Dear Theo,

Enclosed is the letter I was engaged in writing when I received your letter. To which, having read what you say attentively, I want to reply. I’ll start by saying that I think it noble of you, believing that I’m making it difficult for Pa, to take his part and give me a brisk telling-off.

(…)

There’s a desire for peace and for reconciliation in Pa and in you and in me. And yet we don’t seem to be able to bring peace about. I now believe that I’m the stumbling block, and so I must try to work something out so that I don’t ‘make it difficult’ for you or for Pa any more.

I’m now prepared to make it as easy as possible, as tranquil as possible, for both Pa and you.

(…)

You know very well, don’t you, that I consider that you’ve saved my life, that I shall never forget, I’m not only your brother, your friend, even after we put an end to relations that I fear would create a false position, but at the same time I have an infinite obligation of loyalty for what you did in the past by stretching out your hand to me and by continuing to help me.

Money can be repaid, not kindness such as yours.”

Chapel at Nuenen with churchgoers.

This chapel was one of the first scenes Vincent painted in Nuenen. It introduces us to the milieu he was now living in. ”The simple chapel is seen close, yet the artist himself is far enough from the scene to avoid any kind of identification. (..) In painting he was serving “what some people call God, others the Supreme Being, and still others Nature” (letter 133) in his own way.” (Walther & Metzger)

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Sunday, 16 December 1883.

My dear Theo,

Mauve once said to me, ‘you’ll find yourself if you keep on working at art, if you go into it more deeply than you have done so far’. He said that 2 years ago.

I think a lot about those words of his these days.

I have found myself — I am that dog.

Now my idea may be somewhat overstated — the reality less pronounced in its contrasts — less absolutely dramatic — yet I believe the rough character sketch is fundamentally true.

The shaggy sheepdog I tried to get you to understand in my letter yesterday it’s my character, and the animal’s life is my life, if, that is, one leaves out the details and simply gives the essentials.

This may seem exaggerated to you — but I don’t take it back.

For the sake of analysis, no personalities involved, just as a character study, I refer you once more to last summer impartially as if I spoke about strangers rather than about you and me and Pa. I see two brothers walking in The Hague (view them as strangers, other people, don’t think of yourself or of me or Pa).

One of them says, ‘I’m becoming more and more like Pa — I have a certain position to keep up — a certain affluence (very modest in both your case and Pa’s) I must stay in the trade, I don’t believe that I’ll become a painter’. The other says — ‘I’m becoming less and less like Pa — I’m becoming a dog, I feel that the future will probably make me uglier and rougher, and I see “a certain poverty” as my lot — but — but — I will be a painter and, man or dog, in short a being with feeling’.

I tell you, I choose the said dog’s path, I’ll remain a dog, I’ll be poor, I’ll be a painter, I want to remain human, going into nature.”

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Tuesday, 18 December 1883.

My dear Theo,

I received your letter today, as well as a letter from friend Rappard by the same post. Let me start by thanking you for the money. And let me say right after that, that I appreciate it, both in you and in Rappard, that you people approve of my coming here.

This gave me courage at a moment when I myself couldn’t have been more discouraged about that deed, coming here, and had the most lively regret about it, because for my part I saw, deep down in all those conversations I had with Pa, a je ne sais quoi of coolly refusing to commit himself in case of a reconciliation, and this made me desperate because I realized that a cankerous root would remain, which would later make everything impossible, as before, yet again.

But your letter and a very intelligent, very sympathetic, very cordial missive from friend Rappard, and your respective opinions to the effect that my journey here could bring about something good, have led me for the moment to regard the case as not yet being lost, and to employ patience and wisdom.

Have patience with me, brother, and don’t suspect me of unwillingness.”

(…)

The vicarage outbuilding: Vincent’s studio

The circumstances are such, though, that it’s actually urgently necessary to bring about an arrangement that is really kept to. I’ve suggested to Pa that the room that can best be spared should become a storeroom for the bits and pieces that I have and, possibly, a studio (in the event that not I alone but you and I think it desirable and necessary for me to work at home for a while, especially when there are financial reasons to compel us to it).

Business is business, it’s clear enough to both you and me that this is a good move. I haven’t had this haven for far too long, and I believe that it must go ahead if we want to succeed in our plan.

I believe that it can be done, and I’ll dare to embark on it when you and I agree that we must put it into practice, and agree that you won’t hold it against me if, in the event of any discord with Pa, I don’t have to take it as seriously as I took it 2 years ago.

I’ll quietly go my own way, follow your advice not to talk to Pa about various things — only provided that I find in you the person to whom I can talk about them and to whom I can say: I would find this and that all right for this and that reason. THEN I CAN leave Pa out of it, and not talk to Pa about the matters. The ice had to be broken, though, and I did that by coming to Nuenen, and on that occasion I had to have things out with Pa. I’m going to leave it at that, though.

I can tell you now that I’ve managed to get Pa to agree that I can fix up a room here. If you approve, that will become my permanent storeroom, and my studio at times when we don’t have the money to be anywhere else. And I’ll talk to you first, not to Pa, about other changes or matters — and you and I together will get Pa to the point where it will eventually get better and better. I do think you’ll approve my having gone on immediately to bring about something permanent. I think the arrangement where I get a studio here is decidedly good in the circumstances (although I won’t always be in that studio).

So let’s stand by that, and let this letter, and not my last, be our starting-point.”

To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Friday, 21 December 1883.

My dear Theo,

I wanted to drop you a line to tell you that, as a result of the arrangement with Pa and Ma to let me use the room that has until now served as the mangle room as a studio and storeroom for the bits and pieces I have, I’ve come to The Hague to pack up and send my studies, prints, &c. &c. Which I need to attend to myself.

I’ve also spent a day with Rappard who was very cordial, and reassured me not a little concerning some scruples that I had about regarding it as something that might be of a permanent nature.

Well, I saw drawings (watercolours) and painted studies by him that I consider very good.

(…)

I’ve seen the woman again, which I very much longed to do.

I really do feel that it would be hard to begin again.

But that doesn’t alter the fact that I don’t in any way want to act as if I didn’t know her or something.

And I wished that at home they could realize that the bounds of compassion do not lie where the world draws them. You, after all, understood me in this. Given the circumstances, she has behaved bravely since then, a reason for me to forget the problems I had with her from time to time.

And precisely because I can do almost nothing more for her now, I must at least try to put heart into her and fortify her. I see in her a woman, I see in her a mother, and I believe any man who is at all manly must protect such a one if there’s an opportunity to do something. I’ve never been ashamed of it, nor shall I be ashamed of it.

Well, I write in haste. With a handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Wednesday, 26 December 1883.

My dear Theo,

I came back to Nuenen yesterday evening, and now I must get what I have to tell you off my chest straightaway.

I packed up my tools, studies, &c. there and sent them here and, Pa and Ma having cleared out the little room, I’m already installed for the time being in this new workplace, where I hope I may be able to make some progress.

Know also that I spoke to the woman and that it’s our decision, even more definitely, that she will stay by herself and I by myself in any event, so that the world can’t reasonably find fault.

Now that we’ve parted we’ll remain parted, only looking back we regret that we didn’t choose a middle way instead, and even now there remains a mutual attachment that has roots or grounds that go too deep to be transitory.”

1884

JANUARY

Vincent’s mother breaks a leg. Vincent gives her loving care.

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, Thursday, 17 January 1884.

My dear brother,

Something has happened to Ma. Ma hurt her leg getting out of the train.

Pa says the doctor said it was definitely a fracture. And close to the pelvis, in the head of the femur.

I was there when it was set, which went relatively well, so that I almost dare think that it’s more probably a dislocation.

The doctor assures us that there’s no particular danger, but that given Ma’s age it will take a long time.

I wanted to tell you right away how it was, believing that you would prefer it.

But I give you my word that it’s no worse than I say.”

FEBRUARY

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Sunday, 3 February 1884.

My dear Theo,

(…)

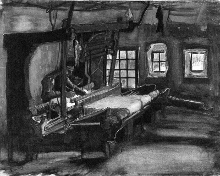

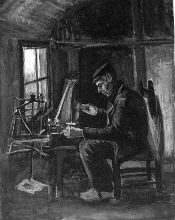

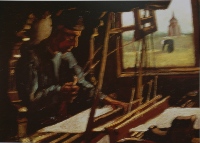

Every day I paint studies of the weavers here, which I think are better in technique than the painted studies from Drenthe that I sent you.

I think those things of the looms with that quite complicated machinery, in the middle of which sits the little figure, will also lend themselves to pen drawings, and I’ll make some as a result of the tip you give me in your letter.

(…)

You will certainly find the fact that I love the countryside here very understandable.

If you ever come I’ll take you into the weavers’ cottages sometime. The figures of the weavers and the women who wind the yarn will certainly strike you. The last study that I made is the figure of a man sitting in the loom on his own, the bust and the hands.

I’m also painting a loom — of old oak gone greenish brown — with the date 1730 carved into it. Next to that loom, by a little window through which one can see a small green field, there’s a high chair, and the little child sits in it, watching the weaver’s shuttle fly back and forth for hours. I’ve tackled that affair just as it is in reality, the loom with the little weaver, the small window and that high chair in the wretched little room with the clay floor.

If you would, write to me in rather greater detail about the Manet exhibition, tell me which of his paintings are to be seen. I’ve always found Manet’s work very original. Do you know Zola’s piece on Manet? I regret that I’ve only seen very few paintings by him. I would particularly like to see his female nudes.

I don’t find it excessive that some people, Zola, for instance, idolize him, although for myself I really don’t think that he can be counted among the very best of this century. Still, it’s a talent that very certainly has its raison d’être, and that’s a great deal in itself. The piece that Zola wrote about him is in the volume ‘Mes haines’. For myself I can’t share the conclusions that Zola draws, as if Manet were a man who’s opening up a new future for modern ideas in art, as it were; to me Millet, not Manet, is that essential modern painter who opened the horizon to many. Regards, with a handshake in thought.

Yours truly,

Vincent

Regards from all — do write to Ma a bit more often, the letters are such a diversion.

“In february 1884 Vincent had agreed to repay Theo’s postal money orders with paintings. (…) Vincent considered his brother the owner of his paintings, while Theo, for his part, saw himself as a trustee.” (Walther & Metzger)

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, between Monday, 18 and Saturday, 23 February 1884.

My dear Theo,

Just a word to tell you that — partly in response to your letter in which you mentioned pen drawings — I have five weavers for you which I’ve made after my painted studies and are slightly different — and I think livelier — in execution than the pen drawings of mine you’ve seen so far.

I’m working on them from early till late, for have also started more new watercolours of them as well as the painted studies and the pen drawings.

I thought about you a lot these last few days, partly on account of a little book that originally came from you and that I borrowed from Lies — the poems of François Coppée. I knew only a very few by him, and they’d already struck me at the time. He’s one of the true artists — who put their heart and soul into it — evident from more than one painful confession. All the more an artist because he’s touched by so many very different things, and is capable of painting both a 3rd-class waiting room full of emigrants who spend the night there — everything drab and gloomy and melancholy — and yet in another mood draws a little marquise who dances a minuet, as elegant as a little figure by Watteau.

That absorption in the moment — that being so wholly and utterly carried away and inspired by the surroundings in which one happens to be — what can one do about it? And even if one could resist it if one wanted to, what would be the point, why shouldn’t one give oneself over to that which is in front of one, as this, after all, is the surest way to create something?

MARCH

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Sunday, 2 March 1884.

My dear Theo,

(…)

You say: the public will be annoyed by this little spot and that, &c. &c. Now listen, that may be so, but this or that bothers you, the dealer, much more than the public in question, I’ve already remarked on that so often — and you start with that. I have to fight my way through, too, Theo, and with you I’m still at precisely, precisely the same level as a few years ago. What you say of my current work — ‘it is almost saleable but’ — is word for word the same as what you wrote to me when I sent you my first Brabant sketches from Etten. So I say — it’s an old file.

(…)

Yes — what am I supposed to think about what you say about my work? For example, I’ll now turn specifically to the studies from Drenthe — there are some among them that are very superficial, I said that myself — but what do I get served up for the ones that were simply painted quietly and calmly outdoors, trying to say nothing in them but what I saw? I get in return: aren’t you too preoccupied with Michel? (I’m talking here about the study of the little hut in the dark and about the largest of the sod huts, namely the one with the little green field in the foreground.) You would certainly say exactly the same thing about the little old churchyard.

And yet, neither looking at the little churchyard nor at the turf huts did I think about Michel, I thought about the subject I was looking at. A subject indeed such that I believe, if Michel had passed by, it would have brought him to a halt and struck him.

For my part, I certainly don’t put myself on a par with master Michel — but I definitely don’t therefore imitate Michel either.

(…)

I’m seeking something calm and something cool in my work. No more than I approve of its just lying about, do I want my work to be displayed in fluted frames in the leading galleries, you see

(..)

Yours truly,

Vincent

Apart from a few years which I find hard to understand myself, when I was confused by religious ideas — by a sort of mysticism — leaving aside that period, I’ve always lived with a certain warmth. Now it’s all becoming bleaker and colder and duller around me. And when I tell you that in the first place I WILL not stand it like this, never mind whether or not I can, I refer to what I said right at the very beginning of our relationship. What I’ve had against you in the last year is a sort of relapse into cold decency, which I find sterile and of no use to one — diametrically opposed to everything that is action, especially to everything that is artistic.

I say it as I see it, not to make you wretched but to get you to see and feel if possible the reason that I no longer think of you as a brother and friend with the same pleasure as before. There has to be more zest in my life if I want to get more brio into my brush — I won’t get a hair’s breadth further by exercising patience. If, for your part, you relapse into the above-mentioned, don’t then take it amiss if I’m not the same towards you as I was in the first year, say.

About my drawings — at this moment it seems to me that the watercolours, the pen drawings of the weavers, the latest pen drawings I’m working on now, aren’t so dull on the whole that they’re nothing at all. But if I come to the conclusion: they’re no good, and Theo is right not to show them to anyone — then — then — it will be all the more proof that I have good reason to dislike our present false position, and will try all the more to change, come what may — better or worse, but not the same.”

To Anthon van Rappard. Nuenen, on or about Tuesday, 18 March 1884.

My dear friend Rappard,

Thank you for your letter — which made me happy. I was pleased that you saw something in my drawings.

(…)

And now the painters — is the purpose and non plus ultra of art those singular spots of colour — that waywardness in the drawing, that which is called distinction of technique? Certainly not. If one takes a Corot, a Daubigny, a Dupré, a Millet or an Israëls — fellows who are certainly the great forerunners — their work is beyond the paint, it stands apart from the chic fellows, just as an oratorical tirade (by, say, a Numa Roumestan) is something very different from a prayer or — a good poem.

One must therefore work on technique in so far as one must say what one feels better, more accurately, more profoundly, but — with the less verbiage the better. But the rest — one needn’t occupy oneself with it.

(…)

I’m afraid that in the future, too — and I congratulate you on it — you will ALSO hear the same comments about technique, as well as about subject and….. everything, in fact, even when that brushstroke of yours, which already has so much character, gets even more.

There are however art lovers who do, after all, appreciate precisely those things that have been painted with emotion.

Although we’re no longer in the days of Thoré and of Théophile Gauthier — alas. Just think about whether it’s wise, particularly nowadays, to talk a lot about technique — you’ll say I’m doing that here myself — actually I do regret it.

But for my part, I intend to tell people consistently that I can’t paint, even when I’ve mastered my brush much better than now. You understand? — especially then, when I really will have an individual manner, more finished and even more concise than now.

I liked what Herkomer said when he opened his own art school — for a number of people who could already paint — he kindly asked his students if they would be so good as to not want to paint like him — but according to their own nature — I am concerned, he says, with setting originality free — not with winning disciples for Herkomer’s doctrine.

Lions do not ape one another.

Well, I’ve painted quite a lot these last few days, a seated girl winding shuttles for the weavers, and the figure of the weaver separately.

I’m longing for you to see my painted studies sometime — not because I’m satisfied with them myself, but because I believe that you’ll be convinced by them that I really am exercising my hand and, when I say I care relatively little for technique, it’s not because I’m saving myself trouble or trying to avoid difficulties. Because that’s not my system.

I’m also longing for you to get to know this corner of Brabant sometime — much more beautiful than the Breda side in my view. It’s delightful here at the moment.

There’s a village here — Son en Breuge- , which is amazingly like Courrières, where the Bretons live — yet the figures over there are at least as beautiful. As one starts to appreciate the form more, one sometimes takes a dislike to — ‘the Dutch traditional costumes’, as they’re called on the photograph albums that they sell to foreigners.

I’m sending you herewith a little booklet about Corot — which I think you’ll enjoy reading if you don’t know it — there are several accurate biographical details in it. I saw the exhibition at the time, for which this is the catalogue.

What’s remarkable in it is that that man ripened and matured for so long. Just look at what he did at different times in his life. I’ve seen examples of his first actual work — itself the result of years of study — honest as the day is long, thoroughly sound — but how people must have despised it! Corot’s studies were a lesson to me when I saw them, and was already struck at the time by the difference from studies by many other landscape painters.

If I didn’t see more technique in your little peasant cemetery than in Corot’s studies — I’d liken it to them. In sentiment it’s identical — an endeavour to express only the intimate and the essential.

What I’m saying in this letter amounts to this — let’s try to get the hang of the secrets of technique so well that people are taken in and swear by all that’s holy that we have no technique.

Let the work be so skillful that it seems naive and doesn’t stink of our cleverness.

I don’t believe that I have reached this desirable point yet, for I don’t even believe that you, who are further on than I am, are already there.

I believe you’ll see more in this letter than nitpicking about words.

I believe that the more one has to do with nature itself — the deeper one penetrates into it — the less attraction one sees in all these studio tricks, and yet, I do want to take them as they are and see them painting. I would really like to spend a lot of time in studios.

“Not in the books have I found it

And from the ‘learned’ — oh, little learned”

is in De Génestet as you know.”

APRIL

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, Wednesday, 30 April 1884.

My dear Theo,

Many happy returns of the day.

It really was important news in your last letter — and I think you’ll be glad that the situation has at least become clearer.

Am really looking forward to your next letter.

As regards the work, I’m doing a fairly large painting of a weaver — the loom straight on from the front — the little figure a dark little silhouette against the white wall. And at the same time also the one I started in the winter, a loom on which a piece of red cloth is being woven — there the loom is seen from the side.

I’ve also started on two others of effects on the heath.

And a thing with Pollard birches.

I’ll have a lot more hard graft on those looms — but in reality the things are such almighty beautiful affairs — all that old oak against a greyish wall — that I certainly believe it’s right that they should be painted. We must make sure that we get them so that the colour and tone match with other Dutch paintings, though. I hope to start on two more of weavers soon, where the figure will appear very differently, that’s to say where the weaver isn’t sitting behind it but is arranging the threads for the cloth. I’ve seen them weaving by lamplight in the evening, which creates very Rembrandtesque effects. Nowadays they have a sort of hanging lamp — but I’ve just got a little lamp from a weaver like the one in The evening by Millet for instance. This is what they used to work by.

I recently also saw coloured pieces woven in the evening — where I’ll take you sometime should you come here. When I saw it, they were also just arranging the threads, so dark, bowed figures against the light, which stood out against the colour of the piece. Great shadows cast on the white walls by the laths and beams of the loom.

Regards — do write soon if you can.

Yours truly,

Vincent

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, between about Monday, 12 and about Thursday, 15 May 1884.

My dear Theo,

I’ve already left it too long before answering your last letter — and you’ll see how it came about. Let me start by saying that I thank you for your letter and for the enclosed 200 francs. And then I’ll tell you that today I’ve just about finished arranging a spacious new studio I’ve rented. Two rooms — one large and one small — en suite.1 I’ve been rather busy because of it this last fortnight. I believe I’ll be able to work a good deal more pleasantly there than in the little room at home. And hope that you’ll approve the step I’ve taken when you’ve seen it.

By the way, of late I’ve continued working hard on the large Weaver — which I mentioned to you recently — and also started a canvas of the little tower you know.

I think what you write about the Salon is very important. What you say about Puvis de Chavannes gives me very great pleasure that you see his work thus, and I’m in complete agreement with you in appreciating his talent.

And as regards the colourists — it’s after all the same with me as with you — I can immerse myself in a Puvis de Chavannes, and yet that doesn’t alter the fact that I should feel the same for Mauve’s landscape with cows and Israëls’s paintings as you feel for them.

As regards my own colour, in the work I’m doing here you’ll find not silvery but rather brown tones (Bitumen, for instance, and Bistre) — which I don’t doubt some people would take amiss of me. But you’ll see for yourself what it’s like when you come. I’ve been so busy painting that recently I haven’t made a single drawing between times.

(…)

Ma is doing very well, in my view — yesterday she came to my new studio in her bath chair. Walking is getting better, although old age considerably frustrates her progress, which continues regularly now, although not as fast as one might think could be the case.

I’ve recently been getting on better with the people here than at the outset, which is worth a great deal to me, for one has a definite need to be able to give oneself a little distraction, and when one feels too lonely the work always suffers in consequence. One must, however, perhaps prepare oneself that these things won’t last for ever.

But I’m in good heart — it seems to me that the people in Nuenen are generally better than those in Etten or Helvoirt — there’s more sincerity here — at least that’s my impression now that I’ve been here a while. People do take a sanctimonious position in what they do — that’s true — but in such a way that for my part I have no scruples about going along with it a bit. And reality sometimes comes very close to the Brabant that one has dreamt.

My original plan of settling in Brabant — which fell to pieces — I must confess is attracting me strongly again. Yet knowing how something like that can collapse, we have to see whether or not it would be an illusion. Anyway, I have enough to do for the time being. I now have the space again to be able to work with a model.

And as to how long it will last, there’s no telling.

Well, regards — the Salon will certainly give you plenty to do, but at the same time also be an interesting time.

Thanks again for what you sent, which I really needed because of this change, by the way. I hope you’ll be able to agree with it when you see how I’ve fitted it out.

Adieu, with a handshake.

Yours truly,

Vincent

Regards from everyone at home, and they ask whether you won’t write to them sometime. Pa has been to Breda; Aunt Bertha was doing well and the dressing had been taken off.”

MAY

Letter 444 (to Theo)

“My dear Theo,

I send you herewith a croquis of a painting I’m working on with some others — this is an effect of trees in blossom in the late afternoon. There are 3 made of the same subject among the drawings that you’ll get as soon as Rappard gets here. What struck me in the scene was the astonishingly authentic and half old-fashioned, half rustic character of this garden. And the reason that I made no fewer than 3 pen drawings of the same little corner, as well as making several studies of it which I destroyed, was precisely because I wanted to convey this character in some intimate details that aren’t expressed easily or as a matter of course or by chance.

If, for my part, I have some self-confidence in my work, it’s also because it costs me too much effort for me to believe that one can’t gain anything by it or does it in vain. And yet again, I shrug my shoulders at the commonplaces into which most connoisseurs increasingly seem to be lapsing.”

Letter 437 (to Rappard)

(…)

“Well, it pleases me that you like my little winter garden. This garden set me so to dreaming, and I’ve since made another of the same subject, also with a little black apparition, which yet again isn’t in it as an example of the structure of the human body worthy of imitating, but as a blotch.”

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Wednesday, 28 May 1884.

My dear Theo,

Just wanted to tell you that Rappard has been here for 10 days or so, and sends you his regards.

As you can imagine, we’ve made several trips together to the weavers and all sorts of fine things outdoors. He was very taken with the scenery here, which is also beginning to appeal to me more and more.

Since he brought the pen drawings with him, I can send them to you now.

Since I made them — even though that’s a relatively short time ago — I’ve got a little out of that way of doing it.

I’ve done nothing but paint recently.

And I’m curious as to whether you’ll see anything in it when you come.

Last winter you wrote to me that you found passages here and there in my watercolours of that time which satisfied you more than before in terms of colour and tone. And then you said something like ‘if you kept that up’.

You’ll see that I’ll very definitely keep it up, and that what was in those watercolours has been strengthened quite a lot in what I’ve painted since.

I’ve just now made a figure of a weaver standing in front of a loom, and one sees the machine behind him.

And I’m working on a landscape of the pond at the bottom of our garden.”

JUNE

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, mid-June 1884.

My dear Theo,

I think I already told you in my last letter that I also wanted to start a large male figure as well as that woman spinning. I now send you a little sketch of it herewith. Perhaps you remember two studies of the same corner, which I already had in the studio when you were here.

I read Les maîtres d’autrefois by Fromentin with great pleasure. And in different places in that book I again found the same questions dealt with that have preoccupied me very much recently, and about which I actually think continually, specifically since, at the end of my time in The Hague, I indirectly heard things that Israëls had said about starting in a low register and making colours that are still relatively dark appear light. In short, expressing light through opposition with dark. I already know what you say about ‘too black’, but at the same time I’m still not completely persuaded that, to mention just one thing, a grey sky always HAS to be painted in the local tone. Which Mauve does; but Ruisdael doesn’t do it, Dupré doesn’t do either. Corot and Daubigny???

Well, as it is with the landscape, so it is with the figure too — I mean, Israëls paints a white wall quite differently from Regnault or Fortuny. And consequently the figure looks quite different against it.

When I hear you talk about a lot of new names, it’s not always possible for me to understand when I’ve seen absolutely nothing by them. And from what you said about ‘Impressionism’, I’ve grasped that it’s something different from what I thought it was, but it’s still not entirely clear to me what one should understand by it.

But for my part, I find so tremendously much in Israëls, for instance, that I’m not particularly curious about or eager for something different or newer.

Fromentin says of Ruisdael that people nowadays are much more advanced in technique than he was. They’re also more advanced than Cabat — who’s sometimes very like R. because of his dignified simplicity, for instance in the painting in the Luxembourg. But does this mean that what R., what Cabat said has become untrue or superfluous? No. The same with Israëls, too — with Degroux, too (Degroux was very simple).

If one says what one says clearly, though, this isn’t enough, strictly speaking.

And saying it with more charm might make it more pleasant to hear (which I don’t disparage, however), but it doesn’t make what is true very much more beautiful, since the truth is beautiful in itself.

(…)

It has bothered me FOR A LONG TIME, Theo, that some of the painters nowadays are taking from us the bistre and the bitumen with which, after all, so many magnificent things were painted, which — properly used, make the coloration lush and tender and generous, and at the same time so dignified. And have such highly remarkable and individual qualities.

At the same time, though, they require that one takes the trouble to learn to use them, for one has to deal with them differently from the ordinary types of paint, and I consider it perfectly possible that many people are frightened off by the experiments that one has to do first, and that naturally don’t succeed on the first day that one starts to use them. It’s now something like a year ago since I started using them, specifically for interiors, but at first they really disappointed me, and yet I always remembered the beautiful things I’d seen in them.

You have a better opportunity than I do to hear about books on art. If you come across good works by people like, say, the book by Fromentin on the Dutch painters, or if you remember any from the past, be aware that I’d very much like you to buy a few sometime, provided they deal with technique — and deduct it from what you usually send. I do intend to learn the theory — I don’t regard it as useless at all, and believe that often what one feels or suspects instinctively leads to certainty and clarity if, in one’s search, one has some guide in truly practical words. Even if there’s just one or a very few things of that nature in a book, it’s sometimes worthwhile not just to read it but actually to buy it, particularly nowadays.

And in the days of Thoré and Blanc there were people who wrote things that are now, unfortunately, already beginning to pass into oblivion.

To mention just one thing. Do you know what an unbroken tone and what a broken tone is? You can certainly see it in a painting, but do you also know how to explain what you see? What they mean by broken?

One should know this sort of thing, theoretically too, be it as a practitioner when painting or as an expert talking about colour.

Most people understand what they want to by it, and yet these words, for instance, have a VERY SPECIFIC meaning.

The laws of colour are inexpressibly splendid precisely because they are not coincidences. Just as people nowadays no longer believe in random miracles, in a God who jumps capriciously and despotically from one thing to another, but are beginning to gain more respect and admiration for and belief in nature, just so and for the same reasons I believe that people should — I don’t say ignore — but thoroughly scrutinize, verify and — — very substantially alter the old-fashioned ideas of innate genius, inspiration &c. in art.

I don’t deny the existence of genius, though, nor even its innate nature. But I do deny the inferences of it, that theory and training are always useless by the very nature of the thing.

I hope, or rather, I’ll try to do the same thing that I’ve now done in the little woman spinning and the old man winding yarn much better later on. Yet in these two studies from life I’ve been a bit more myself than I’ve succeeded in being in most other studies till now (barring a few of my drawings).

As to black — as it happened I didn’t use it in these studies, since I needed a few stronger effects than black, among other things — — and indigo with terra sienna, Prussian blue with burnt sienna actually produce much deeper tones even than pure black. What I sometimes think when I hear people saying ‘there is no black in nature’ is — there doesn’t have to be any black in paint either.

Don’t, whatever you do, get the mistaken idea that the colourists don’t use black, because it goes without saying that as soon as an element of blue, red or yellow is added to black, it becomes a grey, that is a dark red, yellow or blue grey.

Among other things I thought what C. Blanc says in Les artistes de mon temps about Velázquez’s ’s technique was very interesting — that his shadows and half-tones usually consist of colourless cool greys of which black and a bit of white are the chief components — in which neutral, colourless parts the least little dash or hint of red, say, is immediately apparent.

Well — regards, do write soon when you have something to write. It does surprise me rather that you don’t feel as much for Jules Dupré as I wish you did.

I believe so firmly that if I were again to see what I’ve seen by him before, far from finding it less beautiful I would find it even more beautiful than I already did instinctively. Dupré is perhaps even more of a colourist than Corot and Daubigny, although they both are too, and Daubigny really is very daring in colours. But with Dupré there’s something of a magnificent symphony in the colour, carried through, intended, manly. I imagineBeethoven must be something like that. This symphony is surprisingly CALCULATED and yet simple and infinitely deep, like nature itself. That’s what I think about it — about Dupré.

Well — adieu, with a handshake.

Yours truly,

Vincent

AUGUST-SEPTEMBER

Vincent designs six decorative pictures for the dining room of Charles Hermans, an Eindhoven goldschmith.

OCTOBER

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, Thursday, 2 October 1884.

My dear Theo,

Thanks for your letter, thanks for the enclosure. Now listen here.

(…)

Oh — I’m no friend of present-day Christianity, even though the founder was sublime — I’ve seen through present-day Christianity only too well. It mesmerized me, that icy coldness in my youth — but I’ve had my revenge since then. How? By worshipping the love that they — the theologians — call sin, by respecting a whore etc., and not many would-be respectable, religious ladies.

To the one party, woman is always heresy and diabolical. To me, the opposite. Regards.

Yours truly,

Vincent

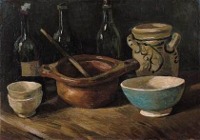

Still life with Clogs and Pots

“Take Mauve — why is he irascible and by no means always mild? I’m not yet as far as he is, but still I’ll get further than I am. I tell you, if one wants to be active, one mustn’t be afraid to do something wrong sometimes, not afraid to lapse into some mistakes. To be good — many people think that they’ll achieve it by doing no harm — and that’s a lie, and you said yourself in the past that it was a lie. That leads to stagnation, to mediocrity. Just slap something on it when you see a blank canvas staring at you with a sort of imbecility.

Still life with three Bottles and Earthenware Vessel

You don’t know how paralyzing it is, that stare from a blank canvas that says to the painter you can’t do anything. The canvas has an idiotic stare, and mesmerizes some painters so that they turn into idiots themselves.

Many painters are afraid of the blank canvas, but the blank canvas is afraid of the truly passionate painter who dares — and who has once broken the spell of ‘you can’t’.

Life itself likewise always turns towards one an infinitely meaningless, discouraging, dispiriting blank side on which there is nothing, any more than on a blank canvas.

But however meaningless and vain, however dead life appears, the man of faith, of energy, of warmth, and who knows something, doesn’t let himself be fobbed off like that. He steps in and does something, and hangs on to that, in short, breaks, ‘violates’ — they say.

For my part — at times like these, when I get completely stuck — I still feel that in a few years’ time I’ll happily dare take on a great many larger bills for paint and other things. I want to have a lot of work — believe me — I have no intention of being bored — do a great deal or die.

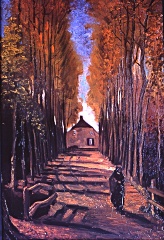

Avenue of poplars

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, Thursday, 9 October 1884.

My dear Theo,

You know well enough that your criticism, at least over the last 1 1/2 years, appears to me to be just a sort of vitriol. Don’t think that I don’t know that against that vitriol one must furnish oneself with a sort of hide that it can’t easily penetrate, and that if one is hardened to it, it doesn’t trouble one much — so — what do I care?

I also believe, moreover, that you mean well. So what more do you want?

I continue just to say this, that I maintain that it’s absolutely not only my fault if the money you give me produces a poor return not only for you, but also a poor return for me.

The former, that it produces a poor return for you, saddens me more than the latter, that it also produces a poor return for me.

It can get better, you’ll say — yes, but then not only I, but also you, will have to change a great deal.

I wanted to let you know that in the winter, perhaps as early as next month, I’m going away from here for a while — I’ve thought about Antwerp — I’ve thought about The Hague.

But in the last few days I’ve thought of something that’s possibly even better.

First of all, I want in any event to have a bit of city life, a bit of a change of scene, since I’ve been either in Drenthe or here in Nuenen for a full year and more. And I believe that this will be a beneficial change for me in general, for my mood, which hasn’t been nor could be as cheerful as I’d like, particularly recently.

Still Life with Four Stone Bottles, Flask and White Cup.

I’ve bought a very fine work on anatomy, Anatomy for artists by John Marshall, which was expensive but which will also be of use to me all my life because it’s very good. What’s more, I also have what they use at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and what they use in Antwerp.

(…)

The key to many things is a thorough knowledge of the human body, but it definitely costs money to learn it. And I think moreover that colour, that chiaroscuro, that perspective, that tone, that drawing, everything in short — certainly also have fixed laws that one must and can study like chemistry or algebra.

This is by no means the easiest view of things, and anyone who says — oh, it must all come naturally — is making light of it.

If that were enough — — But it’s not enough, because however much one knows instinctively, it’s precisely then that one must redouble one’s efforts, in my view, to get from instinct to REASON.”

The Old Cemetery Tower at Nuenen in the Snow

DECEMBER

To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Wednesday, 10 December 1884.

My dear Theo,

(…)

Think about it, old chap — I’m not hiding my deepest feelings from you — I’m weighing up both one side and the other. You can’t give me a wife, you can’t give me a child, you can’t give me work.

Money — yes.

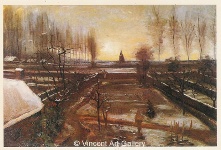

The Vicarage Garden in the Snow

But what good is it to me if I have to do without the rest? It remains sterile because of it, your money, because it’s not used the way I’ve always told you — a labourer’s household if need be, but if one doesn’t make sure that one has a home of one’s own, art doesn’t thrive.

And for my part — I told you really quite plainly enough back in my salad days, if I couldn’t get a fine woman I’d take a common one, better a common one than none.

I know plenty of people who argue the exact opposite, and are as frightened of ‘children’ as I am of ‘no children’.

And for my part — I don’t lightly give up a principle — even if something often goes wrong for me.

And consequently I’m not that afraid of the future because I know how and why I acted in the past. And because I know that there are others who feel the same as I feel.