Arles · 4107 dagen geleden by Ad van den Ende

On 20 February 1888 Vincent reached Arles. When he arrived he found Arles beneath a thick layer of snow. This prevented him the first weeks from working out of doors.

To Paul Gauguin. Arles, Wednesday, 3 October 1888.

“In any event, when I left Paris very, very upset, quite ill and almost an alcoholic through overdoing it, while my strength was abandoning me — then I withdrew into myself, and without daring to hope yet.

At present, dimly on the horizon, here it comes to me nevertheless — hope —that intermittent hope that has sometimes consoled me in my lonely life.”

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, on or about Friday, 2 March 1888

“There’s a hard frost here, and out in the country there’s still snow — I have a study of a whitened landscape with the town in the background. And then 2 little studies of a branch of an almond tree that’s already in flower despite everything.”

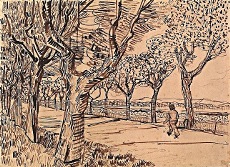

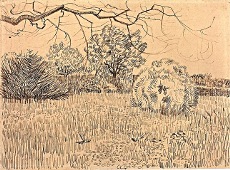

Landscape with path and pollard willows

These willows reminded Vincent of the Dutch willows he often had drawn.

It had been six months since Vincent had made his last serious attempts at drawing. “This makes the Arles drawings all he more surprising. It was here that Van Gogh discovered the reed pen. (…) Van Gogh had already worked with the reed pen in Etten, but he recolls: “I hadn’t such good reed there as here.” Indeed, in all the work he did in the Netherlands there is nothing that resembles the fluid style of drawing that characterisized his work done in Arles.” (Van Heugten)

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Friday, 9 March 1888.

“My dear Theo,

Now at long last, this morning the weather has changed and has turned milder — and I’ve already had an opportunity to find out what this mistral’s like too. I’ve been out on several hikes round about here, but that wind always made it impossible to do anything. The sky was a hard blue with a great bright sun that melted just about all the snow — but the wind was so cold and dry it gave you goose-pimples. But even so I’ve seen lots of beautiful things — a ruined abbey on a hill planted with hollies, pines and grey olive trees. We’ll get down to that soon, I hope.”

Vincent and Japan

In the landscape around Arles Vincent found much that reminded him of Japan. Four weeks after his arrival he wrote to Emile Bernard:

To Emile Bernard. Arles, Sunday, 18 March 1888

“My dear Bernard,

Having promised to write to you, I want to begin by telling you that this part of the world seems to me as beautiful as Japan for the clearness of the atmosphere and the gay colour effects. The stretches of water make patches of a beautiful emerald and a rich blue in the landscapes, as we see it in the Japanese prints. Pale orange sunsets making the fields look blue — glorious yellow suns.”

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, on or about Tuesday, 3 April 1888

“My dear Theo,

I’m in a fury of work as the trees are in blossom and I wanted to do a Provence orchard of tremendous gaiety.”

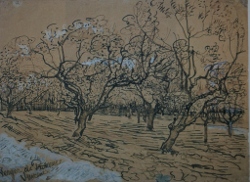

Provinçal Orchard

Following the Japanese artists Vincent often filled in an area with a particular kind of penstroke. By Japanese models inspired he tried in his harvest drawings a combination of pen and patches of colour.

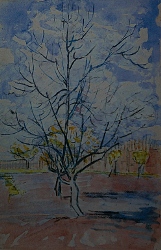

Peach tree in bloom

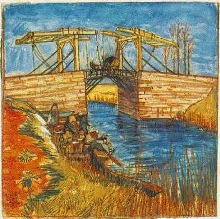

“In order to give Theo an idea of the canvases he was working on, he made a few watercolours after paintings, which he sent him. The Japanese atmosphere was also dominant in these drawings, particularly in the the strong, bright colours to be seen in The Langlois Bridge of April 1888.” (Van Heugten)

The Langlois bridge

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, on or about Friday, 16 March 1888

“As far as work goes, I brought home a no.15 canvas today, it’s a drawbridge, with a little carriage going across it, outlined against a blue sky — the river blue as well, the banks orange with greenery, a group of washerwomen wearing blouses and multicoloured bonnets. And another landscape with a little rustic bridge and washerwomen as well.”

In the second week of April Vincent wrote to Theo that he would have to do “a tremendous lot” of drawing, “because I want to make drawings in the manner of Japanese prints”.

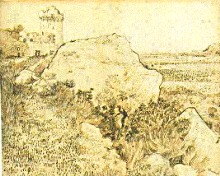

Montmajour; the first series

Soon after he arrived Vincent explored the surroundings and discovered Montmajour, a hill with an impressive ruin of a medieval abbey. He featured this hill in two series of drawings. The first series was done in May 1888.

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Saturday, 26 May 1888.

“I sent you some more drawings today, and I’m adding two more. They’re views taken from a rocky hill from which you can see in the direction of the Crau (an area from which a very good wine comes), the town of Arles and in the direction of Fontvieille. The contrast between the wild and romantic foreground — and the broad, tranquil distant prospects with their horizontal lines, shading off until they reach the chain of the Alpilles.”

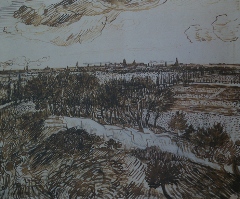

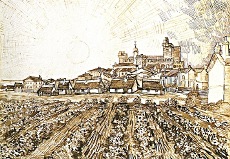

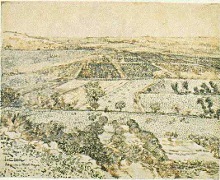

View of Arles from Montmajour

“I’ve just made a drawing even larger than the first two. Of a group of pines on a rock, seen from a hill. Behind that foreground a vista of meadows, a road with poplars and, right in the distance, the town.

The trees very dark against the sunlit meadow.

Perhaps you’ll get a chance to see this drawing. I did it with very thick reed pens on thin Whatman, and used a quill pen for the finer lines in the distance. I can recommend that to you, because the lines with a quill pen are more in the nature of those with a reed.”

Olive trees on Montmajour

The first Montmajour series consisted of seven drawings. Vincent drew them in pencil and reed pen.

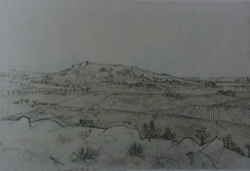

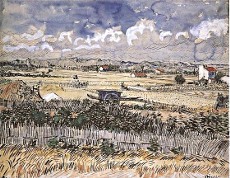

The plain of La Crau

“Some of these works show Van Gogh’s characteristically balanced combination of pencil and ink (…) Japan was constantly in Van Gogh’s thoughts while he was making this series.” (Van Heugten)

A seaside village

View of Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer with the fortified church.

At the end of 1888 Vincent spent a few days at Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer, a Mediterrean fishing village.

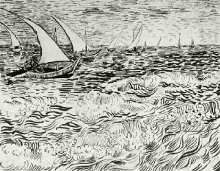

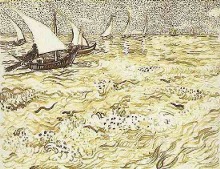

Seascape near Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer

To Emile Bernard. Arles, on or about Thursday, 7 June 1888.

“I’ve finally seen the Mediterranean, which you’ll probably cross before me. Spent a week in Saintes-Maries, and to get there crossed the Camargue in a diligence, with vineyards, heaths, fields as flat as Holland. There, at Saintes-Maries, there were girls who made one think of Cimabue and Giotto: slim, straight, a little sad and mystical. On the completely flat, sandy beach, little green, red, blue boats, so pretty in shape and colour that one thought of flowers; one man boards them, these boats hardly go on the high sea — they dash off when there’s no wind and come back to land if there’s a bit too much.”

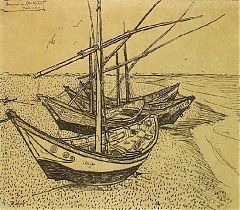

Seascape

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, on or about Tuesday, 5 June 1888

“Now that I’ve seen the sea here I really feel the importance there is in staying in the south and feeling — if the colour has to be even more exaggerated — Africa not far away from one.”

I’m sending you by same post some drawings of Saintes-Maries. I did the drawing of the boats as I was leaving, very early in the morning, and I’m working on the painting, a no. 30 canvas with more sea and sky on the right.

It was before the boats cleared off; I’d watched it all the other mornings, but as they leave very early, hadn’t had time to do it.

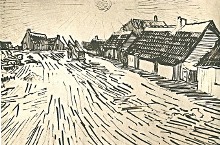

Cottages in Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer

Three cottages

Street in Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer

I have another 3 drawings of huts that I still need and which will follow; these ones of the huts are a bit harsh, but I have some more carefully drawn ones. I’ll make you a consignment of rolled-up paintings as soon as the seascapes are dry.”

(…)

About staying in the south, even if it’s more expensive — Look, we love Japanese painting, we’ve experienced its influence — all the Impressionists have that in common — and we wouldn’t go to Japan, in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all. (…)

I’d like you to spend some time here, you’d feel it — after some time your vision changes, you see with a more Japanese eye, you feel colour differently. I’m also convinced that it’s precisely through a long stay here that I’ll bring out my personality. The Japanese artist draws quickly, very quickly, like a flash of lightning, because his nerves are finer, his feeling simpler. I’ve been here only a few months but — tell me, in Paris would I have drawn in an hour the drawing of the boats? Not even with the frame. Now this was done without measuring, letting the pen go. So I tell myself that gradually the expenses will be balanced by work.

(…)

What Pissarro says is true — the effects colours produce through their harmonies or discords should be boldly exaggerated. It’s the same as in drawing — the precise drawing, the right colour — is not perhaps the essential element we should look for — because the reflection of reality in the mirror, if it was possible to fix it with colour and everything — would in no way be a painting, any more than a photograph.”

The drawings of the view of the village and the boats are executed carefully. In his drawings of the fisherman’s cottages Vincent experimented with a ‘more spontaneus, more exaggerated style’.

“If the drawings that I send you are too stiff, it’s because I did them in such a way as to be able later, if they’re still there, to use them as information for painting.

Fishing boats on the beach

Back in Arles he made a painting of the boats on the beach.

Painting of the boats on the beach

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Tuesday, 12 June 1888.

“I went to Tarascon one day, unfortunately there was so much sun and dust that day that I came home empty-handed.”

The way to Tarascon

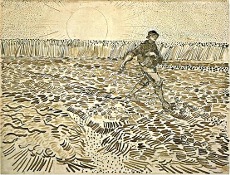

The harvest

In June the wheat was about to be harvested. Vincent saw an opportunity for a new series of drawings and paintings.

“He considered that this subject and that of the sower where the most powerful expressions of country-life (..) He had asked Theo to send him some watercolours becouse he was planning to make pen-and-ink-drawings that he would also colour in – just like Japanese woodcuts.” (Van Heugten)

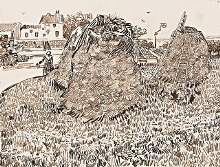

Haystacks in a farmyard

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, on or about Friday, 15 and Saturday, 16 June 1888

“I’ve sent you 3 drawings by post today.

The one with the haystacks in a farmyard will seem too bizarre to you, but it was done in great haste as a project for a painting, and it’s to show you what it’s like.

Now, the harvest is a bit more serious. And that’s the subject I’ve been working on this week, on a no. 30 canvas— it’s hardly done at all — but it kills the rest of what I have, apart from a still life, worked on with patience. MacKnight and one of his friends who’s been in Africa too saw this study today and said it was the best I’d done. Like Anquetin and our friendThomas — you’re really not sure what to think of yourself when you hear people say that…”

The harvest

Vincent was clearly satisfied: he signed his name to the drawing and gave it a title.

He also made a painting of the same subject:

The harvest

This painting was the greatest masterwork Vincent made in Arles.

Figures and heads

Vincent still had a great passion: depicting the human figure. But life in Paris had exhausted him. He wanted first to regain his health before he could devote himself completely to the human figure.

To Arnold Koning. Arles, Tuesday, 29 or Wednesday, 30 May 1888.

“I’m glad you’ve seen my first consignment from here, I hope there’ll be a few seascapes in the next, and then — — — — — the figure.

That’s what I’m chiefly after, only until now walking and working outdoors seemed to me better for my health, and I didn’t want to start a figure until I felt a little stronger.”

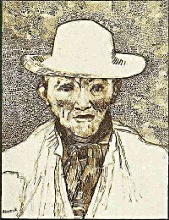

A friend of Vincent, Patience Escalier

Vincent met a Zouave, someone who had faught in Italy for the pope against Garibaldi. He was a tough-looking young soldier in a striking apparel. “a boy with a small face, a bull neck, and the eye of a tiger”, wrote Vincent to Theo. His portrait was one of the most successfully drawn portraits Vincent ever has made. “The man’s head is rendered with a fine pen in a detailed, delicate manner, making an attractive contrast with the rest of the picture, which was drawn quicky using a reed pen.

The Zouave

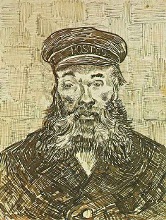

A comparable procedure was used in two other portrait drawings that were also made after paintings: that of his friend,

the postman Joseph Roulin

and one of a girl from Arles, to which he gave the Japanese name

La Mousmé.” (Van Heugten)

Montmajour – a second series

In July Vincent drew a second series of landscapes of Montmajour and the plain of La Crau.

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Thursday, 5 July 1888.

“Yesterday, at sunset, I was on a stony heath where very small, twisted oaks grow, in the background a ruin on the hill, and wheatfields in the valley. It was romantic, it couldn’t be more so, à la Monticelli, the sun was pouring its very yellow rays over the bushes and the ground, absolutely a shower of gold. And all the lines were beautiful, the whole scene had a charming nobility. You wouldn’t have been at all surprised to see knights and ladies suddenly appear, returning from hunting with hawks, or to hear the voice of an old Provençal troubadour.”

Ruins of the abbey of Montmajour

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Sunday, 8 or Monday, 9 July 1888.

“They quibbled with me at the post office, saying that the drawings I was sending you were too big to be sent that way.

I have two large new ones. When there are 6 I’ll send them by rail, in a roll.

…

If the other 4 drawings I have in my head are like the first two I have, then you’ll have the epitome of a really beautiful corner of Provence.”

These six drawings are a high point in his career as a draughtsman. In May he was experimenting with a more fluent and powerful style of drawing.

“This style of drawing culminated in The rock of Montmajour with pine trees; here Van Gogh was working with pencil and a fine pen, but mostly with a reed pen and brush, using grey and black ink. In no other drawing was he to get so close to the character of a Japanese pen-and-ink drawing.” (Van Heugten)

The rock of Montmajour with pine trees

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Monday, 9 or Tuesday, 10 July 1888.

“My dear Theo,

I’ve just come back from a day at Montmajour, and my friend the second lieutenant kept me company. So the two of us explored the old garden and we stole some excellent figs there. If it had been bigger it would have made you think of Zola’s Paradou, tall reeds, grape vines, ivy, fig trees, olive trees, pomegranate trees with fat flowers of the brightest orange, hundred-year-old cypresses, ash trees and willows, holm oaks. Half-demolished staircases, ruined Gothic windows, clumps of white rock covered in lichen, and pieces of collapsed wall scattered here and there in the undergrowth; I brought back another large drawing of it. Not of the garden, though. That makes 3 drawings; when I have half dozen, I will send them.

…

I believe that at this moment I’m doing the right thing by working chiefly on drawings, and seeing to it that I have colours and canvas in reserve for the time when Gauguin comes. I very much wish we could limit ourselves in as little with paint as with pen and paper.

Because I’m afraid of wasting paint, I often spoil a painted study.

With paper — if it’s not a letter I’m writing but a drawing I’m doing — it hardly ever goes wrong: so many sheets of Whatman, so many drawings.”

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, on or about Friday, 13 July 1888

“My dear Theo

I’ve just sent you by post a roll containing 5 large pen drawings. You have a 6th of this Montmajour series. A group of very dark pines and the town of Arles in the background. Later I hope to add a general view of the ruin (you have a hasty croquis of it among the small drawings). Being unable, at this moment when we’re embarking on the partnership with Gauguin, to be of use on the money side, I’ve done all I could to show through work that I take the matter to heart.

As I see it, the two views of the Crau and the countryside along the banks of the Rhône are the best I’ve done with my pen.

…

not everyone would have the patience to let themselves be eaten up by the mosquitoes, and to struggle against this infuriating nuisance of the constant mistral, not to mention that I’ve spent whole days out of doors with a bit of bread and some milk, it being too far to be going back to town all the time.

I’ve already told you more than once how much the Camargue and the Crau — apart from a difference in colour and the clearness of the atmosphere — make me think of the old Holland of Ruisdael’s day. It seems to me that these two sites in the flat countryside, covered with vines and stubble fields, seen from above, will give you an idea of it.

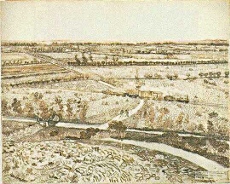

La Crau seen from Montmajour

I assure you that I’m tired out by these drawings; I’ve started a painting too — but no means of doing it with the mistral, absolutely impossible.

…

Please write me a short line straightaway, to know if the drawings have arrived in good condition; they gave me a piece of their mind again at the post office because it was too big, and I’m afraid they’ll perhaps make problems in Paris. All the same, they took them, which pleased me, because after the 14 July holiday you’ll perhaps not be unhappy about refreshing your eye on the expanses of this Crau. The appeal that these vast landscapes have for me is very intense. And so I’ve felt no annoyance in spite of some essentially annoying circumstances, the mistral and the mosquitoes. If a view makes one forget those little vexations, there must be something in it.

However, you see there’s no effect, at first sight it’s a map, a strategic plan as far as workmanship goes.Besides, I also went for a walk there with a painter, who said: now there’s something that would be bothersome to paint. But it must be 50 times that I’ve been to Montmajour to look at this flat view — am I wrong?

I also went for a walk there with someone who was not a painter, and as I said to him: look, to me that’s as beautiful and infinite as the sea, he replied — and he knows it, the sea — I like that better than the sea because it’s just as infinite and yet you feel it’s inhabited.”

To Emile Bernard. Arles, Sunday, 15 July 1888

“Have made large pen drawings — 2 — an immense flat expanse of country — seen in bird’s-eye view from the top of a hill — vineyards, harvested fields of wheat, all of it multiplied endlessly, streaming away like the surface of a sea towards the horizon bounded by the hillocks of La Crau.

It does not look Japanese, and it’s actually the most Japanese thing that I’ve done.

Landscape near Montmajour with train

A microscopic figure of a ploughman, a small train passing through the wheatfields; that’s the only life there is in it. Listen, I passed – a few days after my arrival — that place with a painter friend.

There’s something that would be boring to do, he said. I said nothing myself, but I found that so astonishing that I didn’t even have the strength to give that idiot a piece of my mind. I go back there, go back, go back again — well, I’ve done two drawings of it — of that flat landscape in which there was nothing but………. the infinite… eternity.

Well — while I’m drawing along comes a chap who isn’t a painter but a soldier. I say, ‘Does it astonish you that I find that as beautiful as the sea?’ Now he knew the sea — that one. ‘No — it doesn’t astonish me’ — he says – ‘that you find that as beautiful as the sea — but I find it even more beautiful than the ocean because it’s inhabited.’ Which of the spectators was more the artist, the first or the second, the painter or the soldier — I myself prefer that soldier’s eye. Isn’t that true?”

In these drawings pencil plays a much lesser role than in the first Montmajour series. Vincent was searching for greater clarity of line.

“In the drawings he did in Saint-Rémy, it was also exceptional for him to iuse pencil except as reinforcement.

The drawings reveal a self-assured artist working almost effortlessly.”

(Van Heugten)

The Sower

The yellow house and other townscapes

Vncent did not want to draw the picturesque qualities of Arles, but the aspects of the life in it.

The bank of the Rhône

In April1888 Vincent drew the bank of the Rhône in Arles. It gives an impression of the industry carried on in the small harbour.

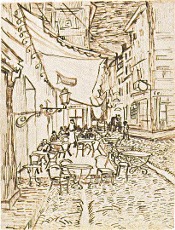

Café terrace on the Place du Forum

This drawing gives a more realist view than the painting of this Café terrace. The painting yields a charming evening scene..

Café terrace at night

The parks

From september 1888 Vincent began to associate the parks in Arles with poets as Dante, Petrarch and Boccacio.

Garden of a public bath

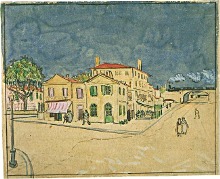

On May 1888 Vincent moved to a house on Place Lamartine.

“The Yellow House was where he hoped to realize the dream that hd been one of his reasons for moving to the South: he wanted to establish an artists’ colony or ”Studio of the South”, where artists could live and work together.” (Van Heugten)

The Yellow House

On 23 October Vincents’ friend Paul Gauguin arrived in Arles. During nine weeks they spent together in the Yellow House. They produced an interesting group of paintings, but their characters conflicted. When Vincent mutilated his left ear Gauguin left Arles as quickly as possible.

The crisis with Gauguin was the first manifestation of a form of epilepsy which would continue for the rest of Vincents’ life.

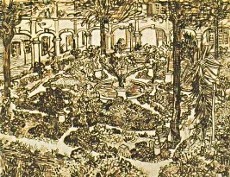

“He was twice admitted to the hospital in Arles and then, at the beginning of May 1889, went to receive treatment in a clinic in Saint-Remy. Shortly beforehand, he did a final, impressive pen-and-ink drawing of the hospital courtyard in Arles. (…)

The hospital courtyard in Arles

The impressive number of drawings Van Gogh produced in Arles, including scores that are of an astonishingly high quality, shows beyond any doubt that his work in the medium of drawing had revealed the same level as his painting.” (Van Heugten)