Vincent in Antwerp Winter 1885 - 1886 · 3902 dagen geleden by Ad van den Ende

In November 1885 Vincent moved to Antwerp and rented a small room above a paint dealer’s shop. He had little money and ate poorly, preferring to spend the money.

While in Antwerp, he applied himself to the study of color theory and spent time in museums, particularly studying the work of Peter Paul Rubens, gaining encouragement to broaden his palette.

Vincent spent three monts in Antwerp.

He bought Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcuts, and incorporated their style into the background of some of his paintings.

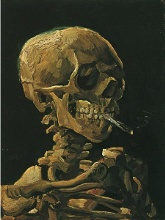

While in Antwerp Vincent began to drink absinthe heavily.

Despite his rejection of academic teaching, he took the higher-level admission exams at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, and, in January 1886, matriculated in painting and drawing. For most of February, he was ill and run down by overwork, a poor diet, and excessive smoking.

To Theo van Gogh. Antwerp, Saturday, 28 November 1885.

Saturday evening

My dear Theo,

Wanted to write to you with a few more impressions of Antwerp. This morning I went for a really good walk in the pouring rain, an expedition with the object of fetching my things from the customs office. The different entrepôts and hangars on the wharves are very fine.

I’ve already walked in all directions around these docks and wharves several times. It’s a strange contrast, particularly when one comes from the sand and the heath and the tranquillity of a country village and hasn’t been in anything but quiet surroundings for a long time. It’s an incomprehensible confusion.

One of De Goncourt’s sayings was ‘Japonaiserie for ever’. Well, these docks are one huge Japonaiserie, fantastic, singular, strange — at least, one can see them like that.

I’d like to walk with you there to find out whether we look at things the same way.

One could do anything there, townscapes — figures of the most diverse character — the ships as the central subject with water and sky in delicate grey — but above all — Japonaiseries.

I mean, the figures there are always in motion, one sees them in the most peculiar settings, everything fantastic, and interesting contrasts keep appearing of their own accord.

(…)

Yours truly,

Vincent

It’s curious that my painted studies look darker here in the city than in the country — is this because the light isn’t as bright anywhere in the city? I don’t know — but it might differ more than one would say on the face of it. It struck me, and I could understand that things that are with you also appear darker than I thought they were in the country. Still, the ones I’ve brought with me now don’t look bad all the same — the mill — avenue of autumn trees and still life, and a few small ones.

To Theo van Gogh, Antwerp, Monday, 14 December 1885.

My dear Theo,

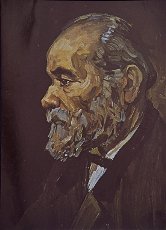

Just wanted to write and tell you that I’ve pressed ahead with models. I’ve made two fairly large heads by way of a trial for a portrait.

Firstly that old man I already wrote to you about — a type of head in the style of V. Hugo’s — then I also have a study of a woman.

In the woman’s portrait I’ve introduced lighter tones in the flesh, white tinted with carmine, vermilion, yellow, and a light background in greyish yellow, from which the face is separated only by the black hair. Lilac tones in the clothes.

Rubens is certainly making a strong impression on me. I find his drawing immensely good, by which I mean the drawing of heads and hands in themselves. I’m utterly carried away, for instance, by his way of drawing the features in a face with strokes of pure red or, in the hands, modelling the fingers with similar strokes. I go to the museum quite often and then look at little else but a few heads and hands by him and Jordaens.

I know that he isn’t as intimate as Hals and ,Rembrandt but those heads are so alive in themselves. I probably don’t look at the ones that are most generally admired. I look for fragments such as those blond heads in St Theresa in Purgatory.”

Head of a Woman with her hair loose

In this painting Vincent achieved a degree of sensitivity that had hitherto been beyond him. The colouring is exquisite. The painting anticipates the rapid brushwork and strong colours of the Paris Period.

To Theo van Gogh. Antwerp, Monday, 28 December 1885.

My dear Theo,

It’s high time that I thanked you for the 50 francs you sent, which enable me to get through the month, even if starting from today it’s pretty much the same again.

But — there are a few more studies done, and I believe that as much as I paint, I also progress by as much. As soon as I received the money I got an attractive model and painted a life-size head. It’s all light except for the black hair. Even so, the head itself stands out in tone against a background in which I’ve tried to get a golden gleam of light.

Here, by the way, is the colour spectrum — a tonal flesh colour, more bronzy in the neck. Jet-black hair — black that I had to make with carmine and Prussian blue, dingy white for the jacket, light yellow, much lighter than the white, for the background.

A touch of flame red in the jet-black hair and a second flame-red bow in the dingy white. She’s a girl from a café chantant and yet the expression I was looking for is a little Ecce Homo-like. But precisely as to expression, although I add my own thoughts, I nonetheless endeavour to remain true, see what I wanted to get into it. When the model came to me, she’d evidently had a few busy nights — she said something that was entirely typical — for my part, champagne doesn’t cheer me up, it makes me very sad.

Then I knew what to do, and I tried to get something voluptuous and sad at the same time.

I’ve now started a second study of the same one, in profile.

Furthermore, I’ve done that particular portrait that I told you I was in discussions about, and a study of that head for myself.

And now I hope to paint a man’s head too, during these last days of the month. I’m in really good spirits, particularly as regards the work, and it’s useful for me to be here.

I imagine that, no matter what these girls may be, one can make one’s money out of them like this sooner than in any other way. There’s no gainsaying that they can be damned beautiful, and it’s in keeping with the spirit of the age that this is the very kind of painting that wins the day.

From the most elevated artistic viewpoint possible, there’s likewise nothing to be said against — painting people, that was the old Italian art, that was Millet and that is Breton.

The question is simply whether one takes the soul or the clothes as one’s starting-point, and whether one allows the form to serve as a clothes-horse for bows and ribbons, or whether one should regard the form as a means of expressing an impression, a sentiment, or whether one models for modelling’s sake because it’s so infinitely beautiful in itself. Only the first is transitory, and the two latter are both high art.

Something that pleased me greatly is — that the girl who posed for me wants a portrait from me for herself, preferably just like the one I did.

And that she’s promised to let me paint a study of her in a dancer’s costume in her room, as soon as she can. Which isn’t possible right now because the man at the café where she works is opposed to her posing, but since she and another girl are going to share rooms, both she and this other girl will want their portraits. And I sincerely hope that it turns out that I do get her back, because she has a remarkable head and is lively. I have to practise, though, because it certainly comes down to dexterity — they don’t have much time or patience — for that matter, the work doesn’t have to be any the worse if it’s put down virtually in one go, and one has to be able to work even when the model doesn’t sit stock still. Anyway. You see that I’m working with a will. If I sold something so that I earned a little more, I’d be able to put even more strength behind it.

To Theo van Gogh. Antwerp, between Tuesday, 12 and Saturday, 16 January 1886.

Peter Paul Rubens Descent from the Cross

My dear Theo,

Last Sunday I saw the two large paintings by Rubens for the first time, and because I’d looked at the ones in the museum repeatedly and at my leisure, these — The descent from the Cross and The elevation of the Cross — were all the more interesting for it.

(…)

But all the same, I adore it because it is precisely he, Rubens, who seeks to express a mood of gaiety, of serenity, of sorrow, and actually achieves it, through the combination of colours — even if his figures are sometimes hollow etc.

Thus in The elevation of the Cross, even — the pale spot — the body a high, light accent — is dramatic in the context of its contrast with the rest, which has been pitched so low.

The same thing, but to my mind far more beautiful, is the charm of The descent from the Cross, where the pale spot is repeated by the blonde hair, pale faces and necks of the female figures, while the sombre setting is immensely rich because of those various low masses, brought together by the tone, of red, dark green, black, grey, violet.

And Delacroix tried again to get people to believe in the symphonies of the colours. And in vain, one would say, judging by how much almost everyone understands good colour to mean the correctness of local colour, the small-minded preciseness — that neither Rembrandt, nor Millet, nor Delacroix, nor whomever you like, not even Manet or Courbet, set as their aim, any more than Rubens or Veronese did.

I’ve also seen various other Rubens paintings &c. in several churches. And it’s very interesting to study Rubens, precisely because he is, or rather seems, so supremely simple in his technique. Does it with so little, and paints — and above all draws, too — with such a swift hand and without any hesitation. But portraits and — heads or figures of women, that’s his forte. There he’s deep and intimate, too. And how fresh his paintings have remained precisely because of the simplicity of the technique.

Now what else shall I tell you? That I feel increasingly inclined, without rushing, that’s to say without rushing nervously — to do all my figure studies over again from the beginning very calmly and coolly. I’d like to get to the point in knowledge of the nude and the structure of the figure where I can work from memory.

Peter Paul Rubens The elevation of the Cross

To Theo van Gogh. Antwerp, Tuesday, 19 or Wednesday, 20 January 1886.

My dear Theo,

Wanted to tell you that Verlat has seen my work at last, and when he saw the two landscapes and the still life that I brought with me from the country, he said — ‘yes, but that doesn’t concern me’ — when I showed him the two portraits, he said — that’s different, if it’s the figure you can come. So I’m going to begin tomorrow by starting work in the painting class at the academy. While I’ve moreover arranged with Vinck (a pupil of Leys’s by whom I saw things in the manner of Leys, medieval) to draw some plaster casts in the evening.

I don’t think I can go wrong with either of these two things — and I can probably learn something there that could be useful to me, be it for painting, be it for drawing. And in any event it’s an attempt to get to know people. I saw in passing that there are several people of my age working in the painting class and in the drawing class. And certainly if I were to become a little friendly with Verlat or Vinck or whomever, it would save me money for models. Anyway — that’s mainly the practical side of the matter.

I also have to go to two people with a view to portraits; I don’t know if anything will come of it.

One is a matter of making two portraits of a couple of very pretty girls — types with very dark eyes, dark hair — two sisters who, I imagine, are being kept.

And the other is a portrait of a married woman. But I tell you, nothing is settled yet and it could fall through.

I do know, though, that if need be I’d be prepared to do them for nothing, just so that I can practise.

To Theo van Gogh. Antwerp, on or about Friday, 22 January 1886.

My dear Theo,

I’ve been painting there for a few days now and it suits me very well. Above all because there are all sorts of painters there, and I see them working in very diverse ways — something I’ve never had — often seeing other people at work.

It’s by far the best for me to stay there for a long time — for the models there are good and it’ll work out better that way.

(…)

In the evenings I go and draw there, too — but I think that the fellows in the drawing class all work badly and in completely the wrong way. The painting class is better, and as I believe I already told you there are all sorts of people of all ages, at least 5 or so even older than me.

At the moment I’m working on a head of a child.

It would be a great help to me if I could have your letter by Monday.

What I wrote to you about clothes I need is also rather urgent.

So far I’ve already made a few acquaintances there, who had seen the things that I’d taken in in order to be admitted. There are devilish good ones among the studies by past students that are hanging there.

This week I painted a large thing with two nude torsos — two wrestlers, a pose set by Verlat. And I really like doing that.

And the same is true of drawing from the antique — I’ve now finished two large figures. At any rate it has two things in its favour — firstly that it interests me greatly, after having drawn clothed models for years, to see the nude and the antique again and to verify things.

Further, just to be admitted anywhere in Paris one has to have been somewhere else and have lost one’s rough edges, and one always has to contend with fellows who’ve already worked at an academy for some length of time.

What Verlat tells me is very severe and so too is what Vinck, who takes the drawing class, tells me — and they strongly advise me above all to draw, if necessary do nothing else but draw from the antique and nudes for at least a year, and that this would be the shortest way, that then I’ll return very differently to my other work outdoors or my portraits.

And I think it’s true — so I have to see to it that I’m somewhere where I have access to both the antique and nude models at first.

The best one in the class has done it like this too, and he says that he felt himself progressing a little with each study, and I’ve been able to see that for myself in things he did before and his recent things.”

To Theo van Gogh, Antwerp, on or about Thursday, 28 January 1886.

(…)

The Greeks don’t start from the outline, they start from the centres, from the cores.

(…)

It’s to search for this — which I wouldn’t want even to talk about with Verlat or with Vinck — that I’m working; there’s no risk that they could show it to me, because the fault with both of them is in the colour which, as you know, isn’t true with either of them.

It’s strange that when I compare my study with those of other people, it has almost nothing in common with them. Theirs have more or less the same colour as the flesh — and so look very accurate from close to — but if one steps back a bit, it becomes painful and flat to look at — all that pink and delicate yellow etc., etc., soft in itself, produces a hard effect.

The way I do it, from close to it’s greenish red, yellow-grey, white, black and a lot of neutral, and mostly colours one can’t put a name to. But if one steps back a little it’s indeed beyond the paint — and then there’s air around it and a restrained undulating light falls on it. At the same time, the least little lick of colour with which one might glaze it is telling.

But what’s lacking in it is — practice — I must paint 50 or so like that — I believe that I’ll have something then. I make the business of putting on the paint too difficult because I haven’t yet sufficiently got into the way of it, have to search too long, work it to death. But this is a question of keeping on painting for a while, so that the touch is effective straightaway as one gets it more fixed in one’s mind.

There are some fellows who’ve seen my drawings — after seeing my peasant figures one of them immediately started drawing the model in the life class with more vigorous modelling, putting the shadows in strongly.

He showed me the drawing and we talked about it. It was full of life and it was the finest drawing that I’ve seen by any of the fellows here. Now do you know what they think about it? The teacher, Siberdt, purposely sent for him and said that if he dared to do it again in that manner it would be considered that he was making a fool of the teacher. And I tell you, it was the only drawing that was generously done, like Tassaert or Gavarni.”

Earlier than planned Vincent left for Paris.